Values and Morality in Global Finance

Money and people's relationships with it have changed a lot since Grandpa stashed his dollars under the mattress. Globalization and evolving technologies are driving a vast system of economic interconnections. Banks are consolidating and the markets are buzzing. Average citizens in the developed world now routinely check the Web to see how their retirement accounts fared overnight, or to rebalance their investment portfolios.

Millions of people are delighted about these changes. Others wonder: Where is my money and what is it doing? Is it supporting a sweatshop somewhere or invested in a polluting industry?

Deep conflicts are emerging about the changing nature of world finance, according to anthropologist Bill Maurer. He believes that people are resisting globalization by creating alternative understandings about money and implementing their ideas in everyday practice.

At the grassroots level, currency advocates are issuing money for use solely in their communities, and neighbors and local businesses accept the local cash alongside the national currency. Other groups have established financial processes that reflect their religious convictions: Islamic banks are providing devout Muslim investors with an appealing alternative to secular institutions. People are forging their own forms of finance.

"These new cultures of finance embrace community and connection while enforcing sharp jurisdictional boundaries around themselves," says Maurer, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of California-Irvine. Maurer's NSF-funded research explores how alternatives to the globalization of finance express community values and sometimes challenge state sovereignty.

Alternative currency dates back to the 1930s and the Great Depression, when barter systems based on local script (instead of faltering national currencies) enabled commerce in the United States and Europe. Such experiments are alive today, supporting novel economic exchanges within communities.

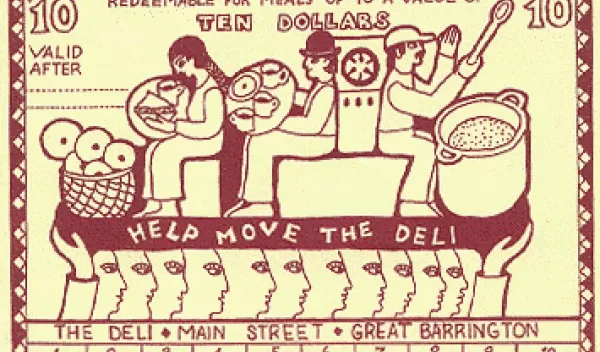

In 1989, for example, Frank Tortoriello, the owner of a popular delicatessen in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, needed funds to relocate his business. When his loan application was rejected by his bank, supporters of the deli led by a local nonprofit group, E. F. Schumacher Society, organized the sale of "Deli Dollars" to patrons. Ten dollars worth of the script was sold for $8 U.S. currency, redeemable over a one-year period. The effort raised $5,000 to cover Tortoriello’s moving costs. Afterward, he paid off his community "loan" by accepting Deli Dollars from his customers at face value: soup and sandwiches, 20 percent off.

In Ithaca, New York, activists have put the adage "time is money" into practice by printing the "Ithaca HOUR," redeemable for $10 worth of plumbing, carpentry, legal advice, or local goods. Hundreds of businesses in the Ithaca area accept HOURS -- including health clubs, farms, restaurants, car rentals, a hospital, and a bowling alley. In fact, printing local currency is not prohibited in the United States, but Ithaca HOURS and other script must be reported as taxable income.

Some advocates of alternative finance prefer to join Local Economic Trading Systems (LETS) rather than print money. In a LETS system members use a centralized record-keeping arrangement (often online) to keep track of their transactions. James Taris, a LETS advocate since 1994, has compiled an international LETS directory listing 1,500 community groups in 39 countries. Whatever system they choose, people are making a statement about money.

"Activists establish alternative economic arrangements in the name of community values and environmental sustainability," says Maurer. For many residents, buying local maple syrup and cordwood with community script is a way to affirm their support for sustainable farming and forestry – and to choose their regional economy over the forces of globalization. The use of local currency is also a social statement: It makes residents more aware of neighborhood resources and history, supports starving artists, and helps people coming off of welfare to find employment in the community.

Religious values can also be expressed through local money. In the late 1990s, a unique form of alternative currency began to circulate in Indonesia. The Koin Emas ONH is a small gold coin designed to help Muslims save money for the pilgrimage to Mecca. For Muslims, the ONH became a way to integrate economic value and religious belief – a kind of religion-specific currency enabling the devout to put their money where their faith is. Ironically, the coin went on sale at state-run pawnshops at a time when Indonesia's national currency, the rupiah, was highly unstable.

Many of the world's one billion Muslims align their financial dealings with religious faith by patronizing Islamic banks that adhere strictly to the teachings of the Koran. Islamic banking prohibits usury and the collection of interest. In the Muslim model, the client and bank form a partnership: Instead of the borrower bearing all of the risk, Islamic banks share the risks and rewards of financing business ventures with their clients.

In Iran and Pakistan, and other Muslim countries, governments have supported or helped to establish Islamic banks because of shared religious values. Islamic banks manage about $200 billion worldwide, according to The Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance.

Maurer's research reveals that Islamic banking is also growing vigorously outside of the Middle East. That’s true even in some non-Muslim nations where the mainstream banks conform to regulations that do not support the model of profit-loss sharing. In the United States and the United Kingdom, some Islamic banks are being supported by donations from successful immigrant businessmen who want to "give back" to their communities.

Islamic banking and community script may or may not be viable in the long-term. Either way, Maurer's research provides valuable insight into how people view money’s universal reach and how some seek to reconcile global capitalism with their notions of community, justice, and faith.

-- Dan Johnson