Dust-on-Snow: On Spring Winds, Something Wicked This Way Comes

On spring winds, something wicked this way comes.

At least for the Colorado Rocky Mountains and their ecosystems, as well as people who depend on snowmelt from these mountains as a regional source of water.

"More than 80 percent of sunlight falling on fresh snow is reflected back to space," says Tom Painter, Director of the University of Utah's Snow Optics Laboratory. "But sprinkle some dark particles on the snow and that number drops dramatically."

That's exactly what's happening in Colorado's high peaks.

When the winds are right and the desert is dry, dust blows eastward from the semi-arid regions of the U.S. Southwest. In a dust-up, Western style, small dark particles of the dust fall on Colorado's pristine white snowfields.

"The darker dust absorbs sunlight, reducing the amount of reflected light and in turn warming the now 'dirty' snow surface," says scientist Chris Landry, Director of the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies (CSAS) in Silverton, Colo.

Painter's and Landry's research on dust-on-snow events, as they're called, is supported by the National Science Foundation's (NSF) division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences, which is part of the directorate for geosciences.

Dust-on-snow events, long recognized as a phenomenon, were little understood despite frequent and regionally extensive dust deposition, says Painter.

Although scientists knew from theory and modeling studies that this dust changed the albedo--the solar energy absorption properties--of snowfields, no one had made measurements of its full impact on snowmelt rates.

Then during the winter/spring of 2004, Painter and Landry began their project.

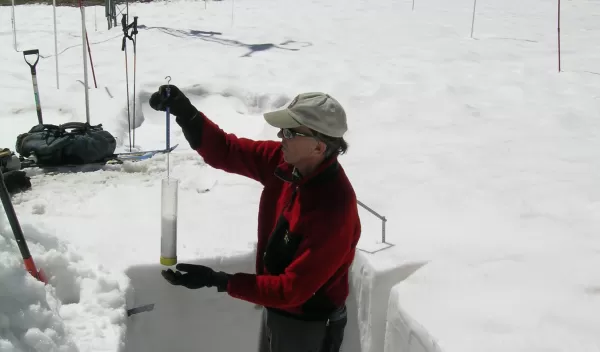

They were the first to make systematic measurements of dust-on-snow events along with complementary climate and hydrologic data.

"Painter's and Landry's observations have confirmed--and most importantly quantified--what many snow and climate scientists had hypothesized but only tested in models," says Jay Fein, program director in NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences.

Spring snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains provides much of the American West's water supplies. As a result of Painter's and Landry's research, water managers have gained new insights into the snowmelt process, and are applying those findings through the Colorado Dust-on-Snow (CODOS) program.

CODOS is based at the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies.

Landry's discussions with water managers led to the development of CODOS, now funded by local, regional, state and federal water management agencies.

CODOS monitors the statewide distribution of dust in mountain snow cover and reports on that distribution in biweekly advisories.

It provides timely analyses of how the dust affects snowmelt timing and rates, and is continuing research driven, in part, by stakeholder questions.

Twelve dust-on-snow events during the winter of 2008/2009 led to a 40 to 50 day earlier snowmelt--which occurred 20 days earlier than normal--with record streamflow rates.

CODOS's monitoring and forecasting services made all the difference, says Fein, enabling water managers to anticipate these events and still provide reliable water supplies.

Wicked, dust-laden winds, already moving westward this spring, no longer blow unfettered. The work of Tom Painter and Chris Landry stands in their way.