Defining a Cyberbully

The following is part one of a three part National Science Foundation series: Bullying in the Age of Social Media.

"I was cyberbullied at age 40 by someone that tried to beat me up in high school," says a person posting on a website that chronicles stories of people intimidated through digital communications.

But I ended up winning the fight, he says. "They held that grudge for 28 years before Googling me, figuring out my employer and sending porn to everyone in the company directory, including clients, with poorly forged headers to look like it was coming from me. My employer was very understanding, but some clients were not."

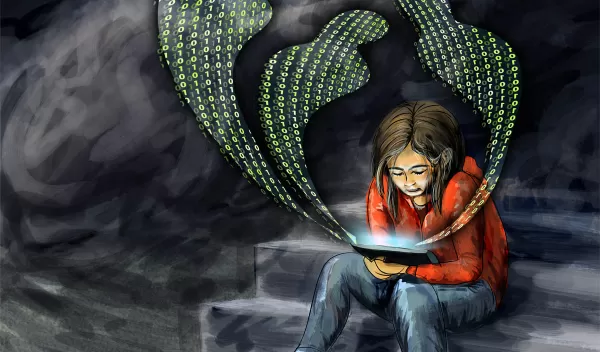

The person telling this story posts under the screen name "Worth." His is one of a growing number of digital incidents causing scholars to examine and define a new type of seemingly invisible and often anonymous, virtual aggression called cyberbullying.

It's a problem primarily among adolescents and it's growing faster than parents, educators or policymakers can effectively respond.

"Cyberbullying and mischief appears to increase with age through childhood and adolescence, so that it is a bigger problem in high school than in junior high," says University of Arizona's Sheri Bauman, one of a number of investigators studying the causes and effects of cyberbullying. "Given that bullying has existed throughout history, it surprises me that we have yet to develop really effective strategies to prevent it."

Traditional bullying and bullying behavior long have existed, but cyberbullying is a relative newcomer. According to a University of Arizona study conducted by Bauman's colleague Robert Tokunaga, about 20-40 percent of all youths report experiencing it at least once in their lives--although some contend the numbers could be higher.

"I think students underestimate their experiences with bullying because it is not fun to view yourself as a 'victim of bullying,' no matter how it is defined," says Justin Patchin, co-director of the Cyberbullying Research Center website. "It is basically suggesting that you are weak or unpopular or inferior in some way. Many people view victims in this light so teens might be reluctant to put themselves in that box."

Moreover, with increasing access to the Internet, cyberbullying doesn't appear to be slowing down. Recent surveys report that at least 80 percent of adolescents own the technology, primarily computers and cell phones, necessary to engage in or be victims of cyberbullying, with even more youth having access at school, libraries or after-school programs.

Significant life challenges result

But being a bully or being bullied is one thing; the consequences of the behavior are another matter entirely. Victims of cyberbullying frequently suffer from a host of negative problems. They have lower self-esteem, higher levels of social anxiety and school absenteeism, as well as greater involvement in drinking, smoking and significant life challenges, according to researchers.

"Both cyber and traditional bullying are predictors of depression and suicide attempts, and those risks exist for both perpetrators and targets," says Bauman, a professor and director of the School Counseling master's degree program at UA.

"Cyberbullying occurs in young people from all socioeconomic groups," she says, "including students with disabilities. Chronic bullying and cyberbullying behaviors, for both perpetrator and victim, may persist into adulthood as well."

This may explain why Worth claims to have been cyberbullied at age 40. But there's a question: does Worth's experience meet a consensus definition of cyberbullying that would allow parents, educators, researchers and policymakers to effectively address the issue?

Practical uses for a consensus definition

Last year, Bauman, acting as principal investigator with funding from the National Science Foundation's Division of Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences, convened an International Cyber Bullying Think Tank in Tucson at the University of Arizona. Twenty-one scholars from eight countries and six U.S. states--psychologists, sociologists, counselors, communication specialists, educators and experts on public health--gathered to define cyberbullying, discuss sampling and research design, examine existing measures and plan future projects.

Their biggest challenge: agreeing on a clear and unambiguous definition. After three days of discussions, think tank participants left with what one participant called "dissent" in coming up with precise wording.

Marilyn Campbell, an attendee from Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, says, "It is important to have a consensus definition of cyberbullying for prevention and intervention efforts." A consensus definition has practical uses "such as in policies or legislation or for research."

Campbell, an associate professor in the School of Learning and Professional Studies, Faculty of Education at QUT argues school anti-bullying policies may not define cyberbullying with sufficient precision. "The nuances of words are important for effective prevention and deterrence, with policy enforcement requiring clarity and precision in language," she says. "School policies may be practically and legally ineffectual if the language used is too vague and does not address the foreseeable risk."

Generally, the language for school policies runs the gamut. Yenton Primary School in Birmingham, England, has a policy that says Yenton school officials believe that all people in the community have a right to learn in a supportive and safe environment without fear of being bullied.

"We believe every individual in school has a duty to report an incident of bullying, whether it happens to themselves or to another person," the policy reads. It goes on to list types of cyberbullying, including text messages, video clips, mobile phone calls, emails, etc.

"Yenton's policy does not define cyberbullying," says Campbell. "They only recount behaviors, which can be difficult as they acknowledge. They might miss some behaviors and as technology changes so do the ways people can bully."

In the United States, the Richland School District in West Richland, Wash., has a very comprehensive school policy that says the district is committed to a safe and civil educational environment free from harassment, intimidation, bullying or cyberbullying.

"The terms harassment, intimidation and bullying shall mean any intentionally written message or other visual communication, verbal communication or physical act, gesture or omission, including but not limited to one shown to be motivated by race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, gender, sexual orientation including gender expression or identity, mental or physical disability or other distinguishing characteristics," the policy begins.

It goes on to define bullying and cyberbullying as acts with the intent to create "a substantial and unjustifiable risk of, creating the threat of, or with the natural end result of physically, emotionally or mentally harming a student, staff member, volunteer, patron," etc.

"The Richland policy is very legalistic and would probably not be all that helpful for parents or students," says Campbell. "There is a middle way of defining cyberbullying."

So what is cyberbullying?

At minimum, researchers say cyberbullying is a subset of aggression that primarily occurs with adolescents. Aggression, as an academic and research construct, refers to intentional behavior that hurts or harms another person. Bullying, meanwhile, refers to aggression where there is also an imbalance of power and repetition of the act; or a "systematic abuse of power."

"Cyber aggression and cyberbullying correspondingly refer to aggression and bullying carried out via electronic media--mobile phones and the Internet," says Peter Smith, a professor of Psychology at Goldsmiths College, University of London. "As such, they are mainly phenomena of the 21st century."

In fact, a 2010 study of cyberbullying found more than 97 percent of young people in the United States have some sort of Internet connection, which is a different measure than owning the technology. The study found youth had access to instant messaging, chat rooms, email, blogs, texting, social networking, online gaming and other media associated with the Internet boom.

Definitions of cyberbullying typically start with three concepts: intent to harm, imbalance of power and usually a repeated action, although some experts replace "repeated action" with "specific targets." While traditional bullying uses these defining characteristics, there is controversy as to whether all these concepts apply to cyberbullying and in what capacity.

For example, the possibility of misunderstanding intent exists more with electronic communication than with traditional bullying because of reduced social cues, social scientists say. The inability to see a smile or a wink on the face of a friend who sent an electronic message could result in the communication being construed as cyberbullying.

"There are also problems with the imbalance of power criterion," says Smith, who led the NSF-sponsored International Cyber Bullying Think Tank's definition subcommittee last year. In traditional bullying, this is usually taken as being in terms of physical strength or psychological confidence in a face-to-face confrontation, or in terms of the number of bullies against one victim.

"These are not so clear in cyberbullying, which is not face-to-face," he says. "There may nevertheless be an imbalance of power either through the anonymity of those committing the act, or if the perpetrators are known by the victim to have relative physical, psychological or numerical strength offline, then an imbalance of power may still be a factor in the victim's perception of the situation."

Smith says in some cases, greater technological expertise could also contribute to an imbalance of power, such as the ability of a bully to develop a website and post mean things about a classmate or a friend. "Although it is easy enough to send emails and text messages," he says, "more sophisticated attacks such as masquerading, or pretending to be someone else posting denigrating material on a website, require more skill."

In one notable example, a 13-year-old Missouri girl, Megan Meier, committed suicide after being harassed through a popular social networking website by a boy she liked. The cyberbully, it turns out, was not a boy at all, but instead was the mother of one of Megan's former friends, who created a false identity to correspond with and gain information about Megan. The mother later used that information to humiliate Megan for spreading rumors about her daughter.

The incident clearly involved issues of anonymity, masquerading and the greater relationship skills possessed by the mother, not the fact that the mother was an adult, which traditionally creates a power imbalance with adolescents.

The third concept, repeated action, also gives some researchers pause. Due to the nature of cyberbullying, the act or behavior may repeat itself without the contribution of the cyberbully, they say.

For example, taking an abusive picture or video clip on a mobile phone may occur only once, but if the person receiving the image forwards it to anyone else, it could be argued that this falls under the category of repetition.

Additionally, if something abusive is uploaded onto a Web page, every hit on that page could count as a repetition. Consequently, the use of repetition as a criterion for traditional bullying may be less reliable for cyberbullying.

"At this point we don't have a standard definition of cyberbullying that is used in research," says Jina Yoon, an associate professor of educational psychology at Wayne State University in Detroit, Mich. She says studies of cyberbullying use different definitions-a situation that can lead to challenges when developing plans or policies that seek to prevent it.

What about Worth's experience?

So where does this leave Worth, who was bullied at age 40? Was his experience cyberbullying?

Yes, but not really says Patchin. "Many people would call this cyberbullying, and it fits within our definition, but we focus on the behaviors as they occur among adolescents. Most researchers reserve the term 'bullying' for repeated harassment as it occurs among adolescents."

Patchin, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, formally defines cyberbullying as willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones or other electronic devices.

"When we measure the behaviors among teens, we tell them that cyberbullying is when someone repeatedly harasses, mistreats, or makes fun of another person online or while using cell phones or other electronic devices," he says.

"We have to be careful about just labeling these incidents without really understanding the relationships," says Yoon narrowing on the characteristics of cyberbullying. "We don't know the history of these two individuals."

"One could argue that the perpetrator is behind the computer with an obvious intent to hurt Worth, which makes him or her more powerful than the victim," she says. But maybe cyberbullying doesn't necessarily fit. "I have heard a broader term such as electronic aggression, which might describe the case better."

Worth's experience exemplifies the current state of cyberbullying research. It remains in need of a consensus definition with social scientists struggling to find one.