Teaching Is in This Scientist's Genes

Humans are inherently curious. From the motion of the Earth to the motion of a tiny motor protein in a cell, we want to know how and why things work. It was this curiosity about the world that attracted me to studying science. For scientists like me, figuring out the intricacies of how nature works is the fun of the job.

This fall, I begin my fourth year as a doctoral student in biophysics at Brandeis University. My research, studying the dynamics of chromosomes found in yeast cells, draws from both my fascination with biology and my love of math. Chromosomes are made up of proteins and genetic material, DNA. They can be thought of as long spaghetti strands that have been stuffed into a small enclosure, the cell nucleus. While we do have information about the structure and chemistry of chromosomes, little is known about their movement in the nucleus, which we imagine to be not unlike spaghetti in a pot of boiling water.

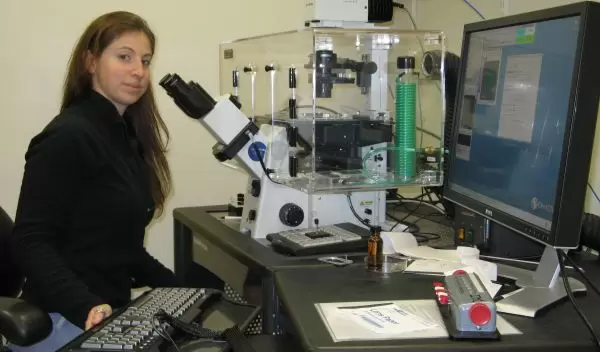

This is where my research enters the picture. In order to visualize chromosomes, we bind light emitting proteins to specific locations along the chromosome. When I take pictures of the cell using a fluorescence microscope, the bright spots I see indicate the position of that location of the chromosome. By combining data from the images with mathematical models, we are beginning to develop a picture of how chromosomes are organized within the nucleus of living cells. My studies will help us understand the physical processes that underlie the repair of broken chromosomes, which are essential to protecting cells from becoming cancerous.

However, as my work has progressed, I have found my main interests shifting. While I enjoy research, I enjoy explaining it to people even more--particularly to non-scientists and young students. I have even been known to sketch my research on napkins during dinner with friends and family. While I possess scientific curiosity, what I truly love is inspiring it in others.

As a former high school math teacher, I had the chance to inspire young minds and encourage students to question the world around them. I realized how important this was to me and have now directed some of my attention to science education and outreach, while continuing to pursue my research.

As a National Science Foundation (NSF) Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) trainee, I had the opportunity to be substantially involved in science outreach. For one year, I worked with a physics teacher at a local high school, helping him to develop curriculum including simple-yet-stimulating lab experiments to be used in his classroom.

In the fall of 2007, I was put in touch with the science educational director at the Discovery Museums located in Acton, Mass., about 20 minutes from Brandeis. I was asked to design a program that went along with their year long theme of "Community Chemistry." To design the program, I drew on the mathematical models of polymers that I use in my research. Polymers are long chain-like molecules that form some of children's favorite toys such as slime and bouncing balls.

The "Bouncy, Sticky, Slimy Chemistry" program was based on these ideas. Students eagerly poked their fingers into sticks of softened butter to learn about states of matter, and had a competition to see whose home-made bouncy ball went the highest. Covered in a mix of laundry soap and glue, I watched them get excited about becoming mini chemical engineers for a few hours while they created a recipe for the perfect slime. For me, hearing young students exclaim, "Wow, science is cool!" is rewarding and fulfilling.

Whether they grow up to be the next generation of neuroscientists or environmental engineers, or simply gain an understanding and appreciation for the subject, getting students of any age enthusiastic about science is important. I plan to use my skills as a scientist and educator to improve science education and excite young, creative minds. While ultimately I won't find the cure to cancer, I find great satisfaction in focusing my energy on educating and inspiring the next generation who just might.

Susannah is a doctoral candidate at Brandeis University, working for Dr. James E. Haber and Dr. Jané Kondev.

-- Susannah Gordon-Messer, Brandeis University sgmesser@brandeis.edu

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.