News Release 07-155

Researchers View Swimming Tactics of Tiny Aquatic Predators

Digital holographic microscopy provides 3-D look at microbes linked to fish kills

Scientists have developed a new way of looking at the plankton that cause red tides and fish kills.

October 26, 2007

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

By applying state-of-the-art holographic microscopy to a major marine biology challenge, researchers have identified the swimming and attack patterns of two tiny but deadly microbes linked to fish kills in the Chesapeake Bay and other waterways.

The study, published in the October 22-26 online Early Edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focused on the aquatic hunting tactics of two single-celled creatures known as dinoflagellates.

Scientists are concerned because these dinoflagellates produce toxins that can kill large numbers of fish, but studying the predators under a conventional microscope is difficult because the tiny animals can quickly swim out of the microscope's shallow field of focus.

In the journal article, the researchers from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute (UMBI) report that they have solved this depth-of-field problem through a technique called digital holographic microscopy, which captures three-dimensional images of the troublesome microbes.

The process enabled the team to identify the tiny predators' distinctly different swimming and hunting tactics.

"The improvement of the digital holographic imaging system was critical for the research," said David Garrison, program director in the National Science Foundation's Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the project. "It markedly improves our ability to understand how microorganisms perform in nature."

"It's like being at NASCAR with a 'magical' pair of binoculars that can keep the entire field of view in focus, so cars both near and far are equally sharp and discernible," said Robert Belas, a microbiologist at UMBI's Center of Marine Biotechnology. "Digital holographic microscopy offers dramatic increases in depth-of-field."

"This is a breakthrough technology in quantifying dinoflagellate behavior," said Allen Place, a biochemist at UMBI's Center of Marine Biotechnology. "We can now begin to look for answers that were previously unattainable."

The research represents a milestone in the application of in-line digital holographic microscopy. This technique consists of illuminating a sample volume with a collimated laser beam and recording the interference pattern generated by light scattered from organisms with the remainder of the beam.

The interference pattern--the hologram--is magnified and recorded by a high-speed digital camera. Computational reconstruction and subsequent data analysis produces three-dimensional views of activity within a small sample of water.

"What's unique is that we were able to use this technique to study the behavior of organisms that are congregated in a dense suspension," said Joseph Katz, a mechanical engineer at Johns Hopkins. "We were able to simultaneously track thousands of these dinoflagellates over time and in three-dimensional space. And we were able to follow individual microorganisms as they swam in complex helical patterns."

Katz and colleagues have developed and implemented digital holography as a means of tracking particles, droplets and organisms in various flows, including measuring behavior of micro-plankton such as dinoflagellates in the ocean.

The lead author of the PNAS article was Jian Sheng of the University of Kentucky, also a visiting scientist at Johns Hopkins.

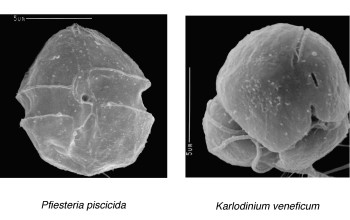

For this project, the team focused on two toxic dinoflagellates: Karlodinium veneficum and Pfiesteria piscicida. Both feed on somewhat smaller non-poisonous microbes commonly found in algal blooms.

The researchers recorded cinematic digital holograms of the two predators alone and in the presence of prey. They found that when a potential meal was nearby, the predators abandoned their random swimming and clustered around their prey.

The team also discovered that Karlodinium microbes moved in both left- and right-hand helices, while the Pfiesteria swam only in right-hand helices.

In addition, the researchers saw starkly different hunting tactics. The Karlodinium appeared to slow down and wait to "ambush" its prey; the speedier Pfiesteria was a more active hunter, increasing its speed and radius of helical trajectories while pursuing its prey.

Just like lions might shift into "stealth mode" when tracking a herd of impala on the African plains, microscopic predators apparently also need to alter their behavior in order to bring down their tiny prey, the researchers concluded.

In the fluid realm of fast-swimming microbes, the scientists said, this study has shown for the first time how the dinoflagellate predators respond to cues and alter the way in which they swim to become more formidable hunters.

Gaining a better understanding of the behavior of these microbes may lead to new ways to avert the fish kills attributed to dinoflagellate toxins.

In addition to Sheng, Belas, Place and Katz, the paper's co-authors are Edwin Malkiel, a research scientist at the Naval Surface Warfare Center, and Jason Adolf of UMBI.

The project was also funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

Phil Sneiderman, JHU, (443) 287-9960, email: prs@jhu.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov