News Release 11-041

Homoplasy: A Good Thread to Pull to Understand the Evolutionary Ball of Yarn

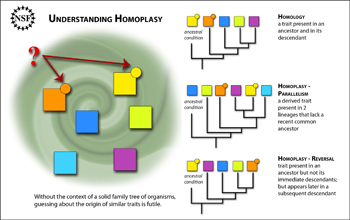

Studying the many potential reasons why the same trait has independently evolved in different species (homoplasy) can improve our understanding of the genetic, developmental and evolutionary relationships among species

An evolutionary tree must be created to determine why two species share the same trait.

February 24, 2011

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

With the genetics of so many organisms that have different traits yet to study, and with the techniques for gathering full sets of genetic information from organisms rapidly evolving, the "forest" of evolution can be easily lost to the "trees" of each individual case and detail.

A review paper published this week in Science by David Wake, Marvalee Wake and Chelsea Specht, all currently National Science Foundation grantees, suggests that studying examples of homoplasy can help scientists analyze the overwhelming deluge of genetic data and information that is currently being generated.

For example, studying situations where a derived trait surfaces in two lineages that lack a recent common ancestor, or situations where an ancestral trait was lost but then reappeared many generations later, may help scientists identify the processes and mechanisms of evolution.

The authors provide many fascinating examples of homoplasy, including different species of salamanders that independently, through evolution, increased their body-length by increasing the lengths of individual vertebrae. By contrast, most species grow longer by adding vertebrae through evolution.

The authors also explain how petals in flowers have evolved on six separate occasions in different plants. A particularly striking example of homoplasy cited by the authors is the evolution of eyes, which evolved many times in different groups of organisms--from invertebrates to mammals--all of which share an identical genetic code for their eyes.

These kinds of examples of genetic and developmental biology help scientists elucidate relationships between organisms, as well as develop a fuller picture of their evolutionary history.

-NSF-

-

The researchers' findings are described in the Feb. 25, 2011 issue of the journal Science.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Lily Whiteman, NSF, (703) 292-8070, email: lwhitema@nsf.gov

Robert Sanders, University of California, Berkeley, (510) 643-6998, email: risanders@berkeley.edu

Principal Investigators

David Wake, University of California, Berkeley, (510) 643-7705, email: wakelab@berkely.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov