Recognizing a Cyberbully

The following is part two of a three part National Science Foundation series: Bullying in the Age of Social Media.

Something is happening on playgrounds, in classrooms, in homes and in every walk of life across America. In fact, it's happening internationally.

"On December 17, 2010, my daughter was a victim of cyber bullying," writes the father of a Virginia girl. "There were four children involved in a chartroom (sic) within their e-mail accounts. One ring leader who seemed rather angry with my daughter started name calling, letting her know nobody liked her, and even went as far as wishing she would die in a hole. This obviously was a very hurtful conversation, which led my 11-year-old daughter to even consider death as an option."

"I was brought out for being a bisexual and made fun of, being told that I'm against God's will and am going to hell," writes a 17-year-old boy from Canada.

"Cyberbullying does not just apply to children. There are adult groups dedicated to harassing and defaming others as well," says an adult woman in an online article titled "The Anonymous Attacks of Adult Cyberbullying Cross the Line and Enter the 'Real World.'" "In November of 2006, my grandfather had a massive heart attack. My way of dealing with my pain was to go online and take it out on nameless, faceless bloggers, and I posted things to people that would probably result in me being beaten up if it were said to someone in 'real life.' When one of these people I attacked told me my grandfather deserved his death, I upped my ante, lashing out at these words with racial slurs, vulgar names and just about anything else you can imagine."

These people, despite their differences, are part of a group that has one thing in common-all of them have been impacted in some way by cyberbullying.

Finding out the who's who of cyberbullying

Social scientists studying cyberbullying say it's a relatively new form of electronic harassment that came to widespread attention in the early 2000s and the short time span in which researchers have looked at the issue leaves them with a number of unresolved questions. Notably, who are the victims and who are the perpetrators?

"We don't have a clear picture of who is most vulnerable," says Sheri Bauman, a former high-school counselor, now a cyberbullying researcher at the University of Arizona. "It takes a bit for a researcher to observe a phenomenon, decide if it merits study, develop a research question, design a study, recruit a sample, gather data, analyze the data and then disseminate it."

There is always a lag between an event and the people who study the event. Nevertheless, even research in progress helps researchers understand both victims and perpetrators and can lead to a better understanding of who is involved. It can also help leaders design initial interventions that prevent the behavior and help victims cope with its effects.

Anonymous bullying clouds identities

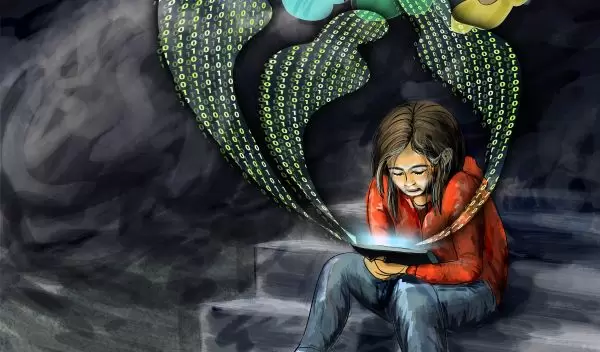

But how would anyone know the identities of perpetrators and potential victims when cyberbullying is largely, almost by definition, anonymous?

In traditional, face-to-face bullying, perpetrators and victims usually know each other because of its physical component--slamming a potential victim into a school locker, for example. Not so in the virtual world; there, cyberbullies have the ability to keep their identities unknown, which creates an asymmetry of information.

In fact, "few youth who reported being a target of Internet aggression reported knowing the harasser in person," writes Michele Ybarra, cyberbullying researcher and president of Internet Solutions for Kids, Inc and her coauthor Kimberly Mitchell in a 2004 study that revealed 69 percent of victims did not know their harasser in person. In contrast, the study says 84 percent of cyberbullies personally know their target.

The finding that such a large percentage of victims do not know their aggressors in person opens the door to more questions about the demographics of cyberbullies and their victims. For instance, one possible trait may be that some cyberbullies are uncomfortable with face-to-face encounters, leaving researchers to question what types of adolescents and adults might fit this description.

Other questions: To what extent do psychological components, such as confrontation avoidance, drive cyberbullies? Are boys or girls more likely to become cyberbullies because of its perceived anonymity? Can finding this information and other information be used to characterize or sketch profiles of potential male and female cyberbullies?

"It's certainly an area that could use more studying," says Bauman.

The role of gender

So, last year, Bauman, acting as principal investigator with funding from the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences, convened an International Cyber Bullying Think Tank in Tucson at the University of Arizona with 21 researchers.

Along with Ybarra, one participant was Faye Mishna, dean and professor of social work at the University of Toronto, whose research focuses on bullying, cyber abuse, cyberbullying and cyber counseling. She says, "One thing that we don't know much about is the role that gender and age play in cyberbullying. But, research has shown both boys and girls are involved."

Researchers say it's expected that both sexes would participate, but what interests them is the number of girls involved. Girls are not thought to be traditional physical bullies.

Other social scientists contend, however, that girls have always played a significant role in traditional bullying but this was not fully recognized until recent research provided additional information. "That was the thinking for a while--that boys were the primary culprits in bullying," says Peter Vishton, a program director in NSF's Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences. "But that wasn't the case at all. Girls just bully differently. The way that boys bully tends to be much easier to see, but there is a different kind of bullying that involves relationships and includes behaviors such as threatening to tell someone's secret to others."

Vishton says new techniques allowed researchers to more closely monitor girls' playground conversations, where they found girls are more likely to spread rumors or gossip as part of bullying. "It turns out, girls bully just as much as boys do." Current thinking about cyberbullying suggests there are different types: physical, verbal and relational bullying. It's this verbal and relational bullying that may typify the type of bullying in which females are more likely to engage.

Mishna agrees. "Boys tend to bully in direct ways such as physical threats, whereas girls are more indirect and do things like spreading rumors or socially isolating a peer," she says. The nature of cyberbullying may lead to participation by more girls and hence more women as the cyberbullies and their victims grow older.

The role of age

Cyberbullying is not only associated with children and adolescents. The Cyberbullying Research Center website run by Justin Patchin, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, and Sameer Hinduja, an associate professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Florida Atlantic University, claims to receive more inquiries from adults than teens.

"We get a lot of emails, phone calls and comments on this blog from adults who are being bullied through technology. They stress to us that cyberbullying is not just an adolescent problem. Believe me, we know," they write on their website.

"We know that cyberbullying negatively affects adults too. It's just that we spend the majority of our efforts studying how this problem impacts school-aged youth due to their tenuous developmental stage," they write.

"While adult cyberbullying is a problem, it's not an emergency situation," Vishton concurs. "There are other issues that need more attention." Still, the researchers acknowledge cyberbullying happens between adults in varied places, from social settings online to electronic, workplace communications.

Judith Fisher-Blando, now with the College of Management and Technology at University of Phoenix, writes that cyberbullying "is not as prevalent in the workplace as bullying behavior is with children and teenagers, but underlying messages and to whom messages are copied can mask a bully's intentions."

Fisher-Blando completed a doctoral research dissertation on the subject in 2008.

Her research found that bullying behavior affects a target's ability to perform his or her job, which can impact the morale of employees and the financial performance of an organization. Moreover, Fisher-Blando's study revealed a relationship between workplace bullying and its effect on job satisfaction and productivity.

In a 2007 Workplace Bullying Institute (WBI)-Zogby survey, 13 percent of U.S. employees reported being bullied in more traditional ways at the time of the survey; another 24 percent said they had been bullied in the past.

It doesn't stop there. An additional 12 percent of workers in the WBI-Zogby survey said they witnessed workplace bullying, while 49 percent reported being affected by it--either being a target or witnessing abusive behavior against a co-worker.

Although social and economic reasons may factor into adult harassment and cyberbullying, researchers from the Project for Wellness and Work-Life contend workplace bullying is not explicitly connected to demographic markers such as sex and ethnicity. In other words, all ages, races, ethnicities and genders are perpetrators and victims of cyberbullying, but what drives them to it?

Motivating a cyberbully

There isn't a lot of information about why people bully online, says Ybarra. "But based on what we know from traditional bullying research, we think that it may be that bullying often occurs to maintain the bully's popularity or social status."

Other motivations include a desire for power. According to Mishna, cyberbullying creates a power imbalance where the cyberbully has some perceived power over the target. She says many adolescents crave this, especially if they are being bullied themselves.

Ybarra adds that retaliation for an incident of traditional bullying also may be a motivating factor. "For some adolescents who are the victims of conventional bullying, the Internet may be a place for them to assert their dominance over someone else in order to compensate for being bullied in person." Ybarra's research finds about half of the self-reported bullies in her study were targets of traditional bullying.

"Perpetrators are more likely to have externalizing problems such as aggressiveness, rule breaking and substance use," adds Ybarra. "These youth may be more likely to have a poor relationship with their caregiver and a low commitment to, or they really don't like, school."

This suggests that youth who harass online are probably experiencing difficulties in other areas of their lives and cyberbullying may not be an isolated behavioral problem. Perpetrators also report higher levels of involvement in traditional bullying than children who are not involved with cyberbullying.

Whatever motivates the cyberbully, anyone with access to the Internet or a cell phone can engage in it. Predictably, this greater use of technology potentially increases the number of targets, who often wonder why they have been singled out for harassment.

Singling out the victims

Just as characterizing a typical cyberbully is a work in progress, so too is it proving difficult to describe a typical victim. While cyberbullying can be the result of a personal dispute between friends that moves from the real world to a virtual one, other victims are singled out merely because of how they look or talk.

"Victims of cyberbullying are often children who don't have a lot of friends," says Mishna of children bullied for anything that makes them different. She says one common characteristic of victims tends to be social isolation. "Anyone who is in a marginalized group is more likely to be cyberbullied."

Almost anything can lead to such marginalization. Adolescents who are disabled, gay, overweight or shy may be targets. Even the way a person dresses or throws a ball can make him, or her, a likely victim of cyberbullying.

Researchers say such marginalization can lead to an odd twist. Children who are on the fringes of mainstream society may be more likely to make social connections through the Internet. This may represent a source of important social support from close online friends. It is possible too that this reliance on virtual social networking can make them even more vulnerable to electronic harassment.