Making room for science at Oklahoma's tribal colleges

More than three centuries ago, when the Comanches ruled America's southern plains, they sought horned toads. Squat, spiked and a tad imposing, the toad--which is actually a lizard--was believed to lead Comanches to buffalo, the tribe's sustenance. Comanches would ask, "Where are the buffalo?" and follow whatever direction the lizard pointed.

More than two months ago, a group of Comanches once again sought horned toads. This time, however, the quest was for science.

The Comanches were a group of high school students in a summer camp hosted by Comanche Nation College (CNC), a tribal college in Lawton, a city in southwest Oklahoma. Led by a biologist from CNC and zoologists from Oklahoma State University (OSU), the students conducted fieldwork on the endangered lizard.

Comanche students from rural schools "don't have as many opportunities to be around the biological sciences," said Gene Pekah, dean of student services at CNC. "So we're going to create those opportunities for them and hopefully create an interest."

The horned toad camp was one such opportunity. A partnership with the state's Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) funded similar camps hosted by CNC.

Funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), EPSCoR promotes development of a state's science and technology resources, boosting competitiveness through collaborations among academia, government and the private sector. Currently, 31 U.S. states and territories have an EPSCoR project.

The program is all about broadening participation in state-of-the-art science, said James Wicksted, associate director of Oklahoma's EPSCoR program and a professor at OSU. According to Wicksted, it made complete sense to partner with the state's tribal colleges because Oklahoma has a large American Indian population, and the state's colleges and universities graduate many American Indian students.

Nationwide, however, American Indian students lag far behind in higher education. According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, less than 1 percent of all science and engineering degrees--bachelor's, master's and doctorates--are awarded to American Indians or Alaskan Natives. Less than 1 percent of American Indian and Alaskan Native students make up the entire U.S. college-age population.

"It's a percent of a percent of a percent type thing," Pekah said.

Weaving science with culture

Oklahoma EPSCoR enriched its tribal outreach after developing summer research programs. The staff wanted to expand the program to tribal students--allowing them to spend part of the summer in labs at the state's main universities, learning sophisticated science--but realized those students often didn't have a solid science background due to a lack of science resources at tribal schools.

"For the students to use the science they learned during these summer programs, they had to know some of the basics," Wicksted said.

So, Oklahoma's EPSCoR, which also partnered with the College of Muscogee Nation (CMN), another tribal college in Okmulgee, due east of Oklahoma City, helped both schools upgrade their facilities with new computers, smart classroom technologies, IT experts and faster networking. The upgrades gave many students their first-ever email address.

Both CNC and CMN are relatively young schools--founded in 2002 and, 2004, respectively--and offer associates degrees. Full-time enrollment at CNC is less than 100 students, while that of CMN is about 200 students. Though many students are tribal members, the colleges serve the entire community. Classes on the language, history and culture of the Comanche and Muscogee tribes are mandatory.

CNC has hosted a variety of summer science camps, some funded through EPSCoR and others through different federal programs. CNC also has an undergraduate research and mentoring program between the college and OSU, funded through grants from NSF's Division of Biological Infrastructure.

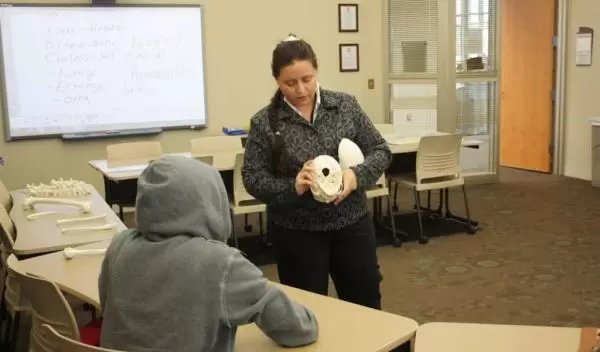

Meanwhile, CMN is creating the school's first-ever science course, teaching biology, human anatomy and physical science.

"There's a lot of enthusiasm" on campus for the classes, said Cynthia Sanders, CMN's new science instructor.

There also are a lot of challenges. Sanders will teach a wide range of students--some with extensive high school experience and some who will set foot in a lab for the very first time at CMN.

"I want them to get the idea that they can be challenged, and they cannot be overwhelmed," she said.

At both schools, great effort has been made to ensure the science is relevant. The horned toad camp blended population studies and DNA analysis with lessons on Comanche culture. A unit on measurement relates to Muscogee words for measuring and their discovery of the concept of zero. Engineering is taught through Comanche teepee structure.

"Taking a science class and integrating it with lessons on history helps students understand their culture and themselves," said CNC president Consuelo Lopez.

Valuing American Indian culture--weaving it within the school curriculum--also helps academics.

"We understand where our students are coming from," said CMN president Robert Bible. As a public school teacher, Bible saw many bright American Indian students lose interest in school, with lessons and teachers disconnected from their heritage.

"[At CMN], we understand the culture, we understand the language," he said. The majority of the staff is Muscogee, and many live within the tribe's boundaries. "That's made a big difference."

Leaders at both CNC and CMN say they want to create opportunities beyond the tribal college.

"They have an understanding that success comes from more than just one class," said Denise Barnes, who heads the EPSCoR program at NSF. Students need flexibility, cultural awareness and experience with the faculty and logistics of four-year schools if they are to advance their education, she said. "Total support has to be there."

CNC and CMN are working hard to ensure that it is. The EPSCoR partnership allows Comanche and Muscogee students to visit Oklahoma's four-year institutions. It gives tribal college students a chance to see firsthand, labs, research and life at a major university. "They see that it's possible," Bible said.

Lopez remembers one student who arrived at CNC knowing he wanted a GED diploma, but not much else. Some science and math classes later, he was hooked. "Now a science major, he has moved on to a bigger school, though he still comes to CNC for classes," she said. "He already has plans to be a scientist."