Even small disturbances can trigger catastrophic hurricanes, researchers find

In a developing hurricane, satellite images show thick white clouds clumping together, arms spinning around a central eye as it heads for the coast.

Florida State University researchers have found that even the smallest changes in atmospheric conditions could trigger hurricanes, also known as tropical cyclones. The information can help scientists understand the processes that lead to these devastating storms.

"The motivation for this research was that we still don't have a universal theoretical understanding of exactly how tropical cyclones form, and to be able to forecast that storm-by-storm, it would help us to have that more solidly taken care of," said Jacob Carstens, a researcher at FSU.

Results of the National Science Foundation-funded study by Carstens and atmospheric scientist Allison Wing are published in the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems.

Current theories on the formation of hurricanes agree that some sort of disturbance must exist to start the process that leads to a hurricane. Carstens used numerical models that started with simple conditions to better understand exactly how these disturbances arise.

"We're trying to go as bare bones as possible, looking at just how clouds organize without any of these external factors to form a tropical cyclone more efficiently," he said. "It's a way we can look at the tropical cyclones themselves rather than the surrounding environment's impact on them."

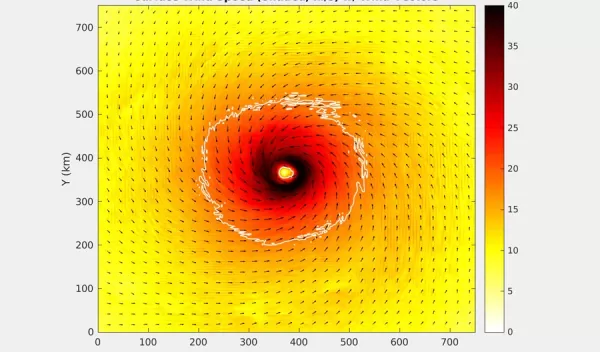

The simulations started with uniform conditions spread across an imaginary box where the model played out. Then the researchers added random temperature fluctuations to kickstart the model and observed how the simulated clouds evolved.

The scientists found that every simulation in latitudes between 10 and 20 degrees produced a major hurricane, even from the stable conditions under which the researchers began the simulation. This happened a few days after a vortex first emerged above the surface and affected its surrounding environment.

"Convection can evidently organize from isolated cotton-ball clouds to a full-blown hurricane without any help from favorable large-scale conditions," said Eric DeWeaver, a program director in NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences. "Sometimes people talk about the 'butterfly effect,' the idea that a butterfly can cause a storm by flapping its wings, but here we don't even need the butterfly."