New technology tracks role of macrophages in cancer spread

Macrophages, cells that help engulf and destroy harmful organisms in the body, tend to be characterized as the Jekyll and Hydes of the immune system.

Macrophages are essential first responders in fighting off infections and marshaling other immune cells to the scene. But they also play a major role in contributing to the growth and metastasis of many cancers, especially breast and pancreatic cancer.

New U.S. National Science Foundation-funded studies at the Morgridge Institute for Research paint a far less simple picture of macrophages, however. Rather than just "good" and "bad" populations, they find a surprisingly wide range of functionality. Better defining those differences may lead to more effective immunotherapies to fight cancer.

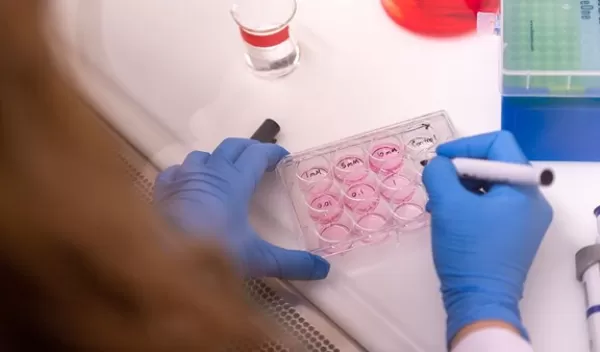

Writing in the journal Cancer Research, researchers Tiffany Heaster, Melissa Skala and colleagues describe using a combination of technologies to better reveal macrophage function and behavior. The team applied fluorescence imaging to measure the precise metabolic activity of cells, then combined it with 3D microfluidic technology, allowing them to see in real time how the cells migrate and what role they play.

Importantly, the technologies helped them identify a distinct population of macrophage cells that migrate actively toward cancer cells in their model -- ones that may have outsized importance in promoting cancer growth. The researchers used both mouse and human cells in the study and found comparable results, indicating this could be a powerful tool for examining the therapeutic potential of macrophages.

"There seems to be more of a spectrum of macrophage phenotypes, and it's been really hard to get at what these phenotypes look like with standard measures," says Heaster. "We need to understand these better before we can target the bad macrophages and promote the good ones."

Today, scientists classify two types of macrophages that operate in the tumor micro-environment. The first, called M1, kills cancer cells through methods such as piercing or eating cancer cells and stimulating secondary immune responses. The second, M2, supports tumor growth by suppressing immune recognition and promoting blood vessel growth, a process called angiogenesis.

Addressing macrophages with immunotherapy would help because they are so diverse and may behave differently from one patient to the next, the researchers say.