Standard water treatment eliminates 'enveloped' viruses

Among the many avenues that viruses, such as the novel coronavirus, can use to infect humans, drinking water may pose only a tiny risk. However, in cases where there is unauthorized wastewater disposal or inadvertent mixing of wastewater with treated water sources, the possibility of transmission through drinking water remains unknown.

Using a coronavirus surrogate that infects only bacteria, researchers at Texas A&M University have now presented strong evidence that existing water treatment facilities can easily reduce vast quantities of the virus, thereby protecting household water from such contagions. In particular, the researchers showed that the water purification step called coagulation could alone get rid of 99.999% of the virus, markedly decontaminating water for consumption.

"We did not want to wait until drinking water became a potential cause for concern for coronavirus transmission," said Shankar Chellam of Texas A&M. "This study shows that decontamination technologies that are already in place in water treatment facilities can remove or inactivate the coronavirus and other viruses that are structurally similar."

Details of the U.S. National Science Foundation-funded study were published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

Viruses can be categorized in two structural types: those that have an outer fortress, called an envelope, and those that do not. Studies have found both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses in wastewater. However, most research has focused solely on the survival of non-enveloped viruses after wastewater and water treatment.

"It is well-known that wastewater mixes with drinking water supplies," Chellam said. "In fact, in many countries, including the United States, wastewater is purified and used as drinking water. If enveloped viruses persist in wastewater, there could be a minuscule chance that these viruses could make it into our drinking water supplies."

For their experiments, the researchers added a coronavirus surrogate to clean water. The surrogate specifically infects bacteria instead of other organisms. Next, the scientists tested the action of a coagulant commonly used in water treatment plants.

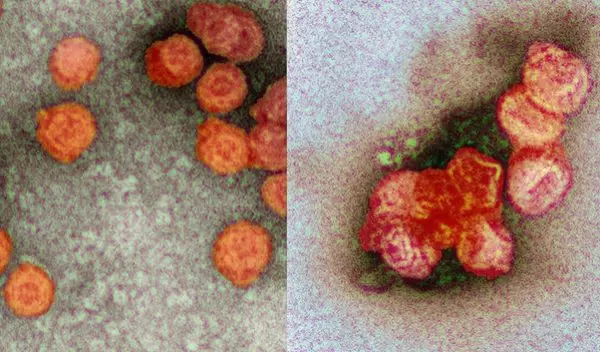

After coagulation, they studied small samples of the virus-infused water under an electron microscope and found that the virus strain assembled on the coagulants, forming clusters. They then checked the presence of infectious viruses in the water after removing the clumps, and found a tremendous reduction.

"In a time of seemingly perpetual uncertainty, it is reassuring to know that our nation's existing wastewater treatment practices are remarkably effective at isolating and removing emerging pathogens such as the novel coronavirus," said Christina Payne, a program director in NSF's Directorate for Engineering.