Study ties solar variability to onset of decadal La Niña events

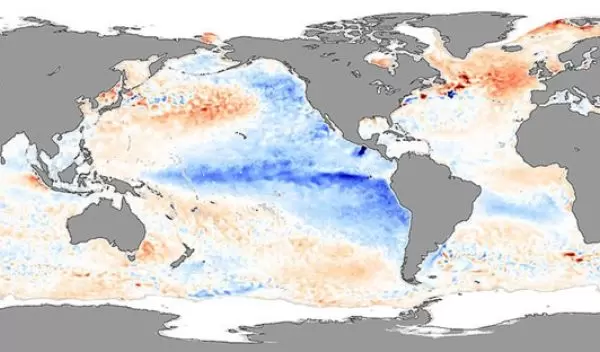

A new study shows a correlation between the end of solar cycles and a switch to La Niña conditions in the Pacific Ocean, suggesting that the sun's variability can drive seasonal weather variability on Earth. The findings were published in the journal Earth and Space Science.

If the connection holds up, it could significantly improve the ability to predict the largest La Niña events, which have seasonal climate effects over land. For example, the southern United States tends to be warmer and drier during a La Niña, while the northern U.S. tends to be colder and wetter.

"Energy from the sun is the major driver of our entire Earth system and makes life on Earth possible," said Scott McIntosh, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, or NCAR, and co-author of the paper. "Even so, the scientific community has been unclear on the role solar variability plays in influencing weather and climate events here on Earth. This study shows there's reason to believe it absolutely does and why the connection may have been missed in the past."

The research was led by Robert Leamon at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and was also co-authored by Daniel Marsh at NCAR. It was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, which is NCAR's sponsor, and NASA's Living With a Star program.

The appearance (and disappearance) of spots on the sun -- the outwardly visible signs of solar variability -- have been observed by humans for hundreds of years. The waxing and waning of the number of sunspots takes place over approximately 11-year cycles, but these cycles do not have distinct beginnings and endings. This fuzziness in length has made it challenging for scientists to match up the 11-year cycle with changes happening on Earth.

In the new study, researchers relied on a more precise 22-year "clock" for solar activity derived from the sun's magnetic polarity cycle, which they outlined as a more regular alternative to the 11-year solar cycle.

The paper does not delve into what physical connection between the sun and Earth could be responsible for the correlation. The authors note there are several possibilities that warrant further study, including the influence of the sun's magnetic field on the cosmic rays that escape into the solar system and ultimately bombard Earth. However, a robust physical link between cosmic ray variations and climate has yet to be determined.

"If further research can establish that there is a physical connection and that changes on the sun are truly causing variability in the oceans, then we may be able to improve our ability to predict La Niña events," McIntosh said.

Maria Womack, a program director in NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences, added that "an apparent coincidence of the sun's magnetic field cycles with the Earth's La Niña climatic cycles. It could lead to a better understanding of the sun's influence on Earth's atmosphere, as well as more accurate predictions of seasonal changes in our weather."