News Release 13-137

Back to the future: Scientists look into Earth's "Deep Time" to predict future effects of climate change

Express concern for Earth's ability to handle rapid changes

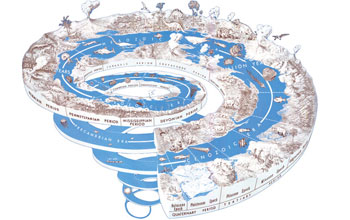

Time spiral: looking back through time to understand future climate change.

August 1, 2013

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

Climate change alters the way in which species interact with one another--a reality that applies not just to today or to the future, but also to the past, according to a paper published by a team of researchers in this week's issue of the journal Science.

"We found that, at all time scales, climate change can alter biotic interactions in very complex ways," said paleoecologist Jessica Blois of the University of California, Merced, the paper's lead author.

"If we don't incorporate this information when we're anticipating future changes, we're missing a big piece of the puzzle."

Blois asked for input from researchers who study "deep time," or the very distant past, as well as those who study the present, to help make predictions about what the future holds for life on Earth as climate shifts.

Co-authors of the paper are Phoebe Zarnetske of Yale University, Matthew Fitzpatrick of the University of Maryland, and Seth Finnegan of the University of California, Berkeley.

"Climate change and other human influences are altering Earth's living systems in big ways, such as changes in growing seasons and the spread of invasive species," said Alan Tessier, program director in the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Environmental Biology, which co-funded the research with NSF's Division of Earth Sciences.

"This paper highlights the value of using information about past episodes of rapid change from Earth's history to help predict future changes to our planet's ecosystems."

Scientists are seeing responses in many species, Blois said, including plants that have never been found in certain climates--such as palms in Sweden--and animals like pikas moving to higher elevations as their habitats grow too warm.

"The worry is that the rate of current and future climate change is more than species can handle," Blois said.

The researchers are studying how species interactions may change between predators and prey, and between plants and pollinators, and how to translate data from the past and present into future models.

"One of the most compelling current questions science can ask is how ecosystems will respond to climate change," said Lisa Boush, program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences.

"These researchers address this using the fossil record and its rich history," said Boush. "They show that climate change has altered biological interactions in the past, driving extinction, evolution and the distribution of species.

"Their study allows us to better understand how modern-day climate change might influence the future of biological systems and the rate at which that change will occur."

While more research is needed, Blois said, changes can be observed today as well as in the past, although it's harder to gather information from incomplete fossil records.

Looking back, there were big changes at the end of major climate change periods, such as the end of the last Ice Age when large herbivores went extinct.

Without those mega-eaters to keep certain plants at bay, new communities of flora developed, most of which in turn are now gone.

"People used to think climate was the major driver of all these changes," Blois said, "but it's not just climate. It's also extinction of the megafauna, changes in the frequency of natural fires, and expansion of human populations. They're all linked."

People are comfortable with the way things have been, said Blois. "We've known where to plant crops, for example, and where to find water."

Now we need to know how to respond, she said, to changes that are already happening--and to those coming in the near future.

-NSF-

-

Scientists are conducting research on organisms from large to small, here a selection of fungi.

Credit and Larger Version -

Researchers are studying climate change effects on organisms and on ecosystems.

Credit and Larger Version -

Will pollinators and other species be able to keep up with the pace of climate change?

Credit and Larger Version -

Tropical forests in places like the Amazon may be hard-hit by future climate change.

Credit and Larger Version -

The researchers' findings are described in the Aug. 2, 2013, issue of Science.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, email: cdybas@nsf.gov

Lorena Anderson, UC-Merced, (209) 228-4406, email: landerson4@ucmerced.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov