Remarks

Dr. Arden L. Bement, Jr.

Director

National Science Foundation

Biography

"Arctic Science: What We Can Do, We Must Do"

Arctic Science Summit Week 2007

Science Day Symposium

Dartmouth College

Hanover, New Hampshire

March 15, 2007

If you're interested in reproducing any of the slides, please contact the Office of Legislative and Public Affairs: (703) 292-8070.

Slide title: Arctic Science: What We Can Do, We Must Do

Slide words: Dr. Arden L. Bement Jr.

Director, National Science Foundation

Arctic Science Summit

March 15, 2007

Slide image: Photo of an iceberg floating in Arctic water

Credit: Martin Nweeia, Narwhal Tusk Research

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Good morning, everyone. I'm delighted and honored to have an opportunity to speak with this distinguished international audience. I'd like very much to thank our Dartmouth hosts for their wonderful hospitality.

Let me begin by mentioning that the National Science Foundation supports extensive programs of research and education both in the Arctic and in Antarctica. The current Arctic Systems Science program dates from 1989, but NSF has supported studies in the Arctic for nearly our entire 50 year history. NSF also provides major support for climate change research, throughout all disciplines and with many international partners.

Credit: IPY (logo); U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (top); Joe Mastroianni, National Science Foundation (bottom)

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

NSF is also the lead agency for International Polar Year Activities in the U.S. Our role is to work closely with other U.S. agencies and other nations worldwide to achieve the vision Articulated by the International Council on Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization and here in the U.S. by the National Research Council of the National Academies of Science.

This National Academies report lays out the U.S. vision for the International Polar Year.

I particularly want to acknowledge the leadership role that Mary Albert played in guiding and informing the report process. 1

The report contains sweeping goals to which many U.S. agencies will contribute, individually and collectively. It reflects a superb understanding of what we need to accomplish, and sets out a clear path to progress.

However, the true potential for progress in Arctic studies lies in joining together as international colleagues to confront the major challenges we face in the Polar regions.

For all these reasons, I consider the Arctic Science Summit to be of extraordinary importance this year. NSF, together with our colleagues from other agencies, has a big stake in Arctic science and education. I have no doubt that is mirrored by the importance every one of you places on these issues.

IPY provides an opportunity to focus worldwide attention on the challenges of understanding the system-scale environmental changes now observed in the Polar regions. Perhaps more importantly, IPY has the potential to generate a concerted worldwide effort to move forward in resolving those challenges. We will need the highest levels of international cooperation, among scientists, educators, and decision-makers, to realize this ambitious undertaking.

Our focus today is on the Arctic. So let me turn my attention to the unique features that confront us in Arctic studies.

Slide title: Arctic Research Stations – 1881-1884

Slide image: Map of the Arctic showing twelve principal research stations and other auxiliary stations established by eleven nations between 1881 and 1884

The stations are: Cap Thordsen, Bossekop, Sodankylä, Karmakuly, Varna, Ssagastyr, Point Barrow, Fort Rae, Fort Conger, Kingua Fjord, Godthaab, Jan Mayen

Credit: NOAA Arctic Research Office

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

The Arctic has long been a focus of international interest. Science and the unending quest to push back the boundaries of the unknown have always tied together those who explore and inhabit Arctic regions. As early as 1881, as shown on this map, there were 12 Arctic research stations around the pole. While primitive viewed by todays standards, research conducted here was by no means without significance. The first instrumented data was collected from the Arctic at about this time -- providing critical continuity with today's data.

Slide title: Installing Instrumentation

Slide image: Aerial photo of researchers walking on an Arctic Ocean ice floe. One researcher pulls an equipment sled

Credit: Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

The sometimes brutal natural challenges and logistical obstacles to living in the Arctic and conducting research there will always prevail. These difficult conditions have long forged bonds between individuals who share the Arctic experience, and have established the basis for mutual cooperation and concern, among the Arctic nations.

Slide title: Arctic Neighbors

Slide image: 3-D map of Earth showing an Arctic polar view. The map shows the Arctic Circle, North Pole, Arctic Ocean and the surrounding nations of Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Russia and USA.

Credit: NASA World Wind

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

A view from the "top" of the world indicates what close neighbors the Arctic nations really are. And like all neighbors the world over, we have common interests.

Among them is evidence that the Arctic is experiencing greater environmental change than any region of the world. The scope and scale of these changes are unprecedented in recorded history. Moreover, the complex and dynamic Arctic system has demonstrated the capacity for rapid, amplified, and unpredictable change, with both local and global implications.

Slide title: The Changing Arctic

Slide image: Landscape photo of the Arctic showing a small boat and icebergs floating in the water

Credit: Martin Nweeia, Narwhal Tusk Research

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Understanding these changes is vital to inform decisions that will shape our response as a global community. And new knowledge, together with the new technology it spawns, is a prerequisite for crafting those solutions intelligently.

We do not yet fully understand the changes occurring in the Arctic. Now is the time to change this. New tools are available to make the needed observations and synthesis. They range from satellites to ships to sensors, and from genomics to nanotechnology, information technology, and advances in remote and robotic technologies.

The litany of Arctic environmental change will be familiar to all of you.

Slide title: Melting Permafrost

Slide image: Aerial photo of melting Arctic permafrost in Siberia

Credit: Karen Frey, University of California, Los Angeles

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

On land, permafrost is melting in some areas, raising questions about possible impacts on seasonal lakes and the wildlife and humans that depend upon them.

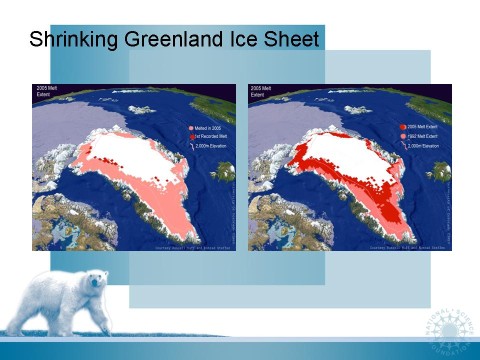

Slide title: Shrinking Greenland Ice Sheet

Slide image: Two maps of Greenland, which compare the melt extent of the Greenland Ice Sheet in 1992 (minimum melt) and in 2005 (maximum melt)

Credit: Courtesy of Russell Huff and Konrad Steffen, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Glaciers in the Arctic are retreating and thinning, a phenomenon that is not confined to the Arctic, but is global in scope. The melting of the Greenland ice sheet raises concerns about rising sea level. There is enough frozen water in Greenland to raise global sea levels seven meters.2

Slide title: Sea Ice Extent

Slide image: A satellite photo showing Arctic permafrost on May 19, 2003.

Credit: NASA

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Sea ice cover in the Arctic is decreasing in extent, a visible indicator of warming. We don't yet understand the complex and multiple feedback mechanisms involved that may influence future climate.

Slide title: Ocean Circulation in the Arctic

Slide image: Map of the Arctic Ocean showing the circulation of cold, relatively fresh water and warmer, denser water

Credit: Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

And as the ice sheet melts, along with other northern glaciers and sea ice, fresher and less dense water flows into the North Atlantic Ocean, creating seawater of lower density. This less dense water may be weakening ocean circulation.

Slide title: Ecosystem Changes

Slide image: Photo showing Alaskan Arctic flora in autumn colors, with the Brooks Range mountains in the distance

Credit: Jim Laundre, Arctic LTER

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Arctic ecosystems show changes, including earlier bloom time for some Arctic flora, and variability in migration for fauna.

Slide image: Photo of a native Alaskan paddling a boat through icy water

Credit: Glenn Williams, Narwhal Tusk Research

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Humans have been an integral part of the arctic polar environment for the last 10,000 or more years. Indigenous peoples as well as other Arctic residents have influenced, and been influenced by, the natural environment. Little is known about the role that environmental extremes play in shaping individual and social behavior. The people of the Arctic are contributing their own valuable observations on change in the region, as these transformations directly affect their everyday lives.

Slide title: Documenting Language and Culture

Slide image: Map of Alaska showing the locations of native languages (left); photo showing an elder native Alaskan talking to two other people in front of a video camera (right)

Credit: Alaska Native Language Center (left); J. Meehan, Narwhal Tusk Research (right)

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

By some estimates, around 70 percent of Arctic indigenous languages are now endangered. Arctic language, culture, and environment create a seamless tapestry, and to lose any thread is to risk losing the whole. Efforts are needed to understand and preserve this rich and valuable heritage.

Slide title: Arctic Voice and Data

Slide image: Two maps of the Arctic region, which compare the traffic on the voice and data communications traffic Iridium Satellite network in the Arctic region in July 2001 (left) and July 2006 (right). The images show the dramatic increase in Iridium-based communications in that region in a span of five years.

Credit: Iridium Satellite

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

This comparison of voice and data transmissions in the Arctic should dispel any lingering belief that the rapid spread of new technologies and the phenomenon of globalization have yet to touch Arctic regions. We need to understand how these profound technological transformations might affect those living in the region. Social and economic change is not a discrete phenomenon, but is woven into the fabric of the complex and dynamic physical and biological systems in the Arctic.

Slide image: Photo of an Arctic landscape of snow and ice with the sun shining low above the horizon

Credit: Peter West, National Science Foundation

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Such change -- whether environmental, biological or social -- has implications for the rest of the globe. Arctic change ripples across the planet on a spectrum of time scales, through the atmosphere, oceans, and living systems. We now know that the Arctic influences dramatically what happens everywhere else on the planet.

Many of today's greatest challenges are inherently global. In the Arctic, this challenge is magnified because Arctic systems are intimately enmeshed with the vast biogeochemical cycles that sustain life on the planet -- most particularly, with climate cycles.

It is not only possible to make progress, it is urgent that we do so. Nobel Prize-winner Paul Crutzen has coined the phrase "Anthropocene Age"3 to describe the present day as the first geological era in which human actions have resulted in impacts on our environment that are planetary in scale. In todays climate of high-velocity change and rising expectations, we need to acknowledge the constraints that sustainability puts on our actions.

For these reasons, climate change research and environmental observations in the Arctic will be a major focus for NSF IPY activities. We are only beginning to understand the full extent of the impacts that climate change may have on the environment, and even less is known about effects on human health, the spread of infectious diseases, and the economy.

We have the knowledge and tools to advance our understanding, and we recognize the urgency of the task. Another ingredient is necessary to move forward. We will need to strengthen, deepen and expand international collaborations in order to meet the extraordinary challenges that confront us in the Arctic -- and across the planet.

Discovery is no longer the purview of one scientist, one institution, or one nation. It is increasingly the result of connections that criss-cross the globe. The very conduct of science and engineering has changed, as boundaries between disciplines blur, and increasingly novel discoveries occur in the unexplored territory where different fields of science and engineering converge. Thanks to our enhanced communications technologies, the science and engineering community is now global in scope.

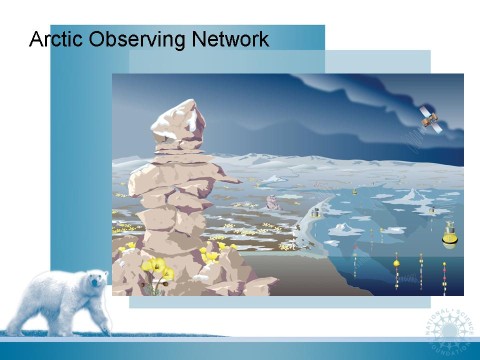

Slide title: Arctic Observing Network

Slide image: Illustration showing the Arctic Observing Network in an Arctic landscape. The illustration shows buoys and sensors transmitting data to a satellite. An Inuit rock pile called an "Iniksuit" is in the left foreground.

Credit: Nicolle Rager Fuller, National Science Foundation

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

An important case in point is the planned pan-Arctic Observing Network, or AON -- an effort to significantly advance our observational capability in the Arctic. As a means to address the key questions of SEARCH, the Study of Environmental Arctic Change, AON will help us document the state of the present climate system, and the nature and extent of climate changes occurring in the Arctic regions. The result will create a long-term legacy for future generations of scientists and policy-makers.

Slide title: Instrumentation on the Ice

Slide image: Photo of two researchers from the Center for Remote Sensing of Ice Sheets (CReSIS) with a radar system that is used to map near-surface snow accumulation layers in the Greenland Ice Sheet

Credit: D. Braaten, CReSIS, University of Kansas

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

NSF, together with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is developing atmospheric, land and ocean-based environmental monitoring capabilities that will be key components of the planned network. AON will include a network of human observations and indigenous knowledge in the Arctic.

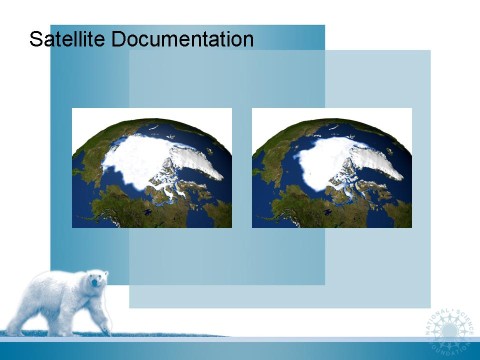

Slide title: Satellite Documentation

Slide image: Two visualizations based on satellite data comparing the Arctic sea ice minimums in 1979 (left) and in 2005 (right)

Credit: NASA

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

In approaching this enormous task, we will need to draw on every available resource. Satellite data from NASA, for example, have greatly informed our understanding of climate change -- most notably, by documenting changes in the Greenland ice sheet. NASA is working closely with space agencies around the world in order to bring the enormous capability of their combined assets to bear on IPY climate change research.

A circum-polar observation network will also require collaboration among all Arctic nations, and the participation of those living in the Arctic region. The task is simply too large for any one nation to undertake. Important observational data are required from many sites around the pole. Change is taking place across the region, and it is essential that we measure and analyze change on a correspondingly fine geographical scale. New data will help refine the output from computer climate models, giving us more accurate predictions of change on a regional basis. This information is especially critical to Arctic communities.

Slide title: Indigenous Peoples

Slide image: Photo of two reindeer herders with their reindeer in Arctic Russia

Credit: Patty A. Gray

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

There are many other pressing issues on the Arctic research agenda that require international collaboration. One important objective is to increase our understanding of the place of humans in the Arctic system. Humans and polar communities have adapted to life in the polar environment, which for much of the year is both cold and dark.

What factors contribute to vulnerability, resilience, and sustainability of human cultures in the Arctic is an important question of deep interest not only to researchers but especially to those who reside in the Arctic. Also important are a host of questions about human and social dynamics. One example is how settlement patterns in Polar regions affect education and the development of human capacities.

Of course, the need for fundamental understanding extends to all Arctic life, from humans to microorganisms.

Another critical area of research is the investigation of ocean circulation in the Arctic and North Atlantic. I could name many more. The list of Arctic research needs is long.

Slide title: International Collaboration

Slide image: 3-D map of Earth showing an Arctic polar view. The map shows the Arctic Circle, North Pole, Arctic Ocean and the surrounding nations of Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Russia and USA.

Credit: NASA World Wind

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Progress will depend critically on how we work together.

Our ability to work on global scales is, in large measure, a result of revolutionary advances in computer, information and communication technologies. In time, a comprehensive cyberinfrastructure will connect the international community seamlessly. We need to improve substantially the complement of cyberinfrastructure in the Arctic, particularly as we move forward with an Arctic Observation Network.

Arctic teamwork begun through research and education can lead to broader cooperation among nations -- in policies for the oceans, the environment, and the full scope of human influences on the planet. International collaboration at its best generates new, often unforeseen opportunities for further partnerships. It is also an important way to quicken the pace of research when results are urgently needed.

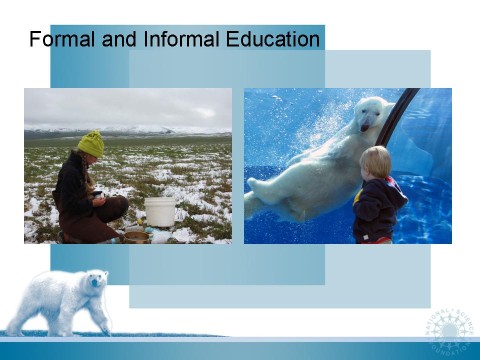

Slide title: Formal and Informal Education

Slide image: Photo of a woman sampling macroinvertebrates in the Upper Kuparuk watershed, North Slope, Alaska (left); photo of a child and a submerged polar bear looking at each other through a clear wall in a Detroit Zoo aquarium (right)

Credit: Adrian Green, USGS (left); Dave Hogg (right)

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

I have yet to mention education. International Polar Year activities present an extraordinary opportunity to educate young people and the public about science and technology and its significance for the future of the planet. The monumental challenges and extremes of the Arctic, its mystery and diversity, its many cultures, its unique flora and fauna -- all of these features can fire the imagination and engage our youngsters in the excitement of discovery and exploration.

It is no longer adequate simply to inform young minds. We now have the ability -- and the responsibility -- to engage children in the discovery process, in the classroom and the field, at museums and aquaria, and in the home.

And as science and technology take on ever greater significance in our lives, it is increasingly important to have an educated public that appreciates the role that discovery plays in ensuring a sustainable, healthy and prosperous world.

Slide image: Photo of a polar bear walking along a narrow strip of land between two bodies of water on the coast of the Beaufort Sea, Alaska

Credit: Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Slide background image: Polar bear

Slide background credit: Based on photo by Susanne Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Design by: Adrian Apodaca, National Science Foundation

Science and technology have always been a powerful force for human progress. Today, more than ever before in history, we have the knowledge and technology to unravel the staggering complexities that pervade the Arctic system. Much of the leadership required to make progress on all of these fronts is here in this room. Each of us -- and each of our institutions, organizations and nations -- have a critical role to play in IPY and beyond.

Fifty years ago, the International Geophysical Year established the notion of scientific diplomacy -- the idea that scientists and engineers, working in international partnership could solve problems of mutual concern and could further the interests of peace and cooperation among nations. That was also a time of heroic exploration, when Dr. Vivian Fuchs and Sir Edmund Hillary successfully completed their trans-Antarctica expedition, a feat which had long remained a dream after Shackleton's disastrous attempt.

Today, we have crossed the threshold into a new era of exploration -- an era of discovery very different than that of Fuchs and Hillary. The explorers of the 21st Century are opening new conceptual frontiers in science and technology.

Another half century into the future, a new generation will judge the diligence and wisdom with which we pursue our opportunities for progress and meet our challenges. At NSF, we look forward to being part of the winning team with our colleagues and friends around the globe.

It is my very strong belief that 50 years on, the next generation of Arctic explorers will be able to look back on a full century of cooperation, friendship and scientific progress. Our deliberations today and -- more importantly -- our actions tomorrow will be a vital part of that legacy.

![]()

1 Mary Albert, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, Hanover, New Hampshire. Dr. Albert chairs the U.S. Committee for IPY. She is also affiliated with Dartmouth College.

Return to speech

2 David Talbot, "Seeing Greenland," MIT Technology Review, March/April 2007, p.24.

Return to speech

3 Crutzen, Paul; Nature 415, 23, 2002.

Return to speech