All Images

News Release 09-205

Ancient Lemurs Take Bite Out of Evolutionary Tree

The fossil primate Darwinius and a new find, Afradapis, are not related to humans

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

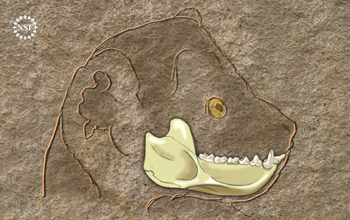

Artist's reconstruction of the lower jaw of a 37 million-year-old Egyptian primate, Afradapis.

Credit: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (939 KB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.

Stony Brook University paleontologist, Erik Seiffert, explains that while some students of the early primate fossil record consider adapiforms to be closely related to Old World monkeys, apes and humans, they actually developed similar features independently through a process called convergent evolution.

Credit: Dena Headlee/National Science Foundation

Palentologist Erik Seiffert and his research team recently uncovered the fossils of a new adapiform primate, which they describe as a distant relative to current day lemurs.

Credit: Credit: Walter Jetz, UCSD

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (10.3 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.

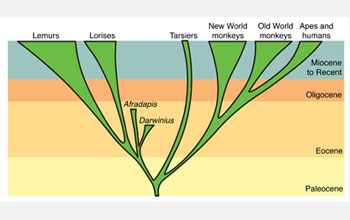

Using a method called parsimony analysis to reconstruct the most likely family tree of living and extinct primates, taking into consideration virtually all of the available anatomical evidence that can be observed, palentologists determined that Darwinius and its now extinct relatives, including Afradapis, are not on the evolutionary lineage leading to Old World monkey's, apes and humans, but instead are more closely related to the living lemurs and lorises.

Credit: Erik Seiffert, Stony Brook University

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (745 KB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.

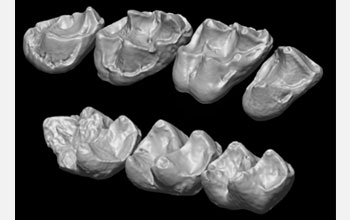

Students of the early primate fossil record generally hold two views about the evolution of an extinct group of lemur-like primates called adapiforms. A majority of students consider adapiforms to be ancient relatives of a primate suborder that includes lemurs and lorises. A minority view is that adapiforms are more closely related to monkeys and apes. The latter hypothesis hinges on features such as fusion of the two halves of the jaw, reduction and loss of the first few premolar teeth, and the presence of incisors. Researchers say their studies of the jaw and teeth of the adapiform Afradapis shows that adapiforms and the distant relatives of monkeys and apes independently evolved similar features.

Credit: Erik Seiffert, Stony Brook University

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (187 KB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.

Paleontologists searched an area near the Fayum Depression in northern Egypt about 40 miles outside Cairo for clues to the primate evolution tree.

Credit: Erik Seiffert, Stony Brook University

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (1 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.