News Release 08-019

Fossil Record Suggests Insect Assaults on Foliage May Increase with Warming Globe

With implications for present climate, new data links past spike in temperature with increased voraciousness of plant-eating insects

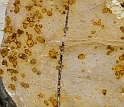

During a warming spike more than 55 million years ago, insects chewed large holes in this leaf.

February 11, 2008

This material is available primarily for archival purposes. Telephone numbers or other contact information may be out of date; please see current contact information at media contacts.

More than 55 million years ago, the Earth experienced a rapid jump in global carbon dioxide levels that raised temperatures across the planet. Now, researchers studying plants from that time have found that the rising temperatures may have boosted the foraging of insects. As modern temperatures continue to rise, the researchers believe the planet could see increasing crop damage and forest devastation.

The researchers, from Penn State, the Smithsonian Institution, the University of Maryland, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Wesleyan University published their findings in the Feb. 11, 2008, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Our study convincingly shows that there is a link between temperature and insect feeding on leaves," said lead author Ellen Currano of Pennsylvania State University and the Smithsonian Institution. "When temperature increases, the diversity of insect feeding damage on plant species also increases."

With support from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Currano collected the study fossils from the badlands of Wyoming, gathering more than 5,000 fossil leaves from five sites representing time zones before, during and after the roughly 100,000 year temperature spike called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).

The researchers found that the PETM plants were noticeably more damaged than fossil plants before and after that period. The PETM plants, many of which are legumes -- the family that now includes beans and peas -- show damage with greater frequency, greater variety (such as mining, galling, surface feeding and other assaults) and a more destructive character than plants from the surrounding geologic time periods.

"This study shows that insects responded rapidly to a major change in climate during the PETM," said Enriqueta Barrera, program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences, which helped fund the project. "This is in agreement with previous findings by [co-author] Scott Wing of the Smithsonian Institution who found that plants that previously were common much farther south migrated northward at this time"

In order to test alternative reasons for the increased damage, the researchers looked at whether the plants in the analysis had key traits that made them more palatable to insects. However, after using established analytical techniques to measure various leaf structures in all of the specimens, the researchers concluded that the PETM plants do not appear to vary structurally from the plants in the rock layers above and below the temperature spike.

The researchers also looked to see if the insect species feeding on the leaves changed over the time period. The analysis showed that what changed was the abundance of insect species that are highly specialized in the type of plant they consume and the way they consume it, such as leaf miners and gallers - they are far more abundant in the PETM.

"We wanted to see whether the increase in insect damage during the PETM was because the leaves were less tough or more nutritious," said Currano. "There is no evidence to support this. Instead, we think that the warming allowed insect species from the tropics, particularly those that feed in a highly specific manner, to migrate north."

Biologists are already aware that insects in the tropics consume more plants and that warming temperatures are causing organisms to widen their ranges. In addition, research has shown that plants grown under higher concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) are less nutritious, so insects must eat more plant tissue to get the same sustenance. These earlier studies support the recent findings about the PETM.

Because food webs that involve plant-eating insects affect as much as three quarters of organisms on Earth, the researchers believe that the current increase in temperature could have a profound impact on present ecosystems, and potentially to crops, if the pattern holds true in modern times.

"This study represents a highly integrative approach, using well-studied systems, to model ecological dynamics during upcoming climate shifts," said William Hahn, a program director in NSF's Division of Graduate Education who supported Currano's work with a research fellowship. "The truly relevant description of past climate-change effects on plant-insect interactions, specifically the probability of increased insect damage to plants with rising temperatures, is a forward-looking approach that will help us prepare for the effects of future global warming," he added.

In addition to Currano's Graduate Research Fellowship, the research team was supported by grants from NSF's Division of Earth Sciences, as well as funding from the Roland Brown Fund of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, the Evolving Earth Foundation, the Paleontological Society, Penn State, the Petroleum Research Fund, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the University of Pennsylvania.

-NSF-

-

Ellen Currano collecting fossil leaves from a site that is 57 million years old in Wyoming.

Credit and Larger Version -

This image was captured as the researchers were pulling into camp after a full day in the field.

Credit and Larger Version -

Approximately one third of this legume leaf was consumed by insects during the PETM.

Credit and Larger Version -

An insect mined into this from the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.

Credit and Larger Version -

This fossil legume leaf from the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum shows examples of galls.

Credit and Larger Version

Media Contacts

Joshua A. Chamot, NSF, (703) 292-7730, email: jchamot@nsf.gov

A'ndrea Elyse Messer, Penn State University, (814) 865-9481, email: aem1@psu.edu

Program Contacts

William J. Hahn, NSF, (703) 292-8545, email: whahn@nsf.gov

Enriqueta C. Barrera, NSF, (703) 292-8551, email: ebarrera@nsf.gov

Principal Investigators

Ellen Currano, Penn State/Smithsonian Institution, (202) 633-1380, email: CURRANOE@si.edu

The U.S. National Science Foundation propels the nation forward by advancing fundamental research in all fields of science and engineering. NSF supports research and people by providing facilities, instruments and funding to support their ingenuity and sustain the U.S. as a global leader in research and innovation. With a fiscal year 2023 budget of $9.5 billion, NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to nearly 2,000 colleges, universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives more than 40,000 competitive proposals and makes about 11,000 new awards. Those awards include support for cooperative research with industry, Arctic and Antarctic research and operations, and U.S. participation in international scientific efforts.

Connect with us online

NSF website: nsf.gov

NSF News: nsf.gov/news

For News Media: nsf.gov/news/newsroom

Statistics: nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards database: nsf.gov/awardsearch/

Follow us on social

Twitter: twitter.com/NSF

Facebook: facebook.com/US.NSF

Instagram: instagram.com/nsfgov