Remarks

Dr. Cora Marrett

Acting Director

U.S. National Science Foundation

Biography

"A Learning Society: Can America Get Its Bounce Back?"

Revitalizing Chemistry Education for Competitiveness and Diversity

American Chemical Society Fall Meeting

Washington, D.C.

August 17, 2009

If you're interested in reproducing any of the slides, please contact the Office of Legislative and Public Affairs: (703) 292-8070.

Title slide: A Learning Society: Can America Get its Bounce Back?

NSF Responds to the American Recovery & Revitalization Act

Slide words: Dr. Cora Marrett, Acting Deputy Director, National Science Foundation Revitalizing Chemistry Education for Competitiveness and Diversity American Chemical Society Annual Meeting, August 17, 2009

Slide image: photo of a cyberenvironmentSlide image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

Greetings to everyone. I'm delighted to be with you this afternoon for a dialogue on revitalizing education. The American Chemical Society has been a leading voice for educational reform, and I urge the continuation of the good work. Excellence in science, technology, engineering and mathematics education is critical to our nations future.

I've titled my remarks today "A Learning Society: Can America Get Its Bounce Back?"

Slide title: A Learning Society

Slide words: Embraces learning for everyone, everywhere; values learning as a path to prosperity; honors learning as a fundamental right; and welcomes learning as a driver of progress.

Slide images: 2004 photo of a Research Experiences for Undergraduates participant at the Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems (MBES) Engineering Research Center (left); photo of a chalkboard with mathematical equations (center); photo of a young girl experimenting with static electricity (right)

Slide image credits: Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems Engineering Research Center (left); GettyImages/PhotoDisc/Lawrence Lawry (center); Nanoscience Program, University of Arkansas (right)

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

By a "learning society" I mean:

- A society that embraces learning as a fulfilling and rewarding activity of everyday life, for everyone, everywhere.

- A society that values learning as a path to national prosperity, and thus as a top priority on the national agenda.

- A society that honors learning as a fundamental right and promotes policies to ensure that all citizens have the opportunity to develop their full potential.

- A society that welcomes learning as a basis for progress, and is willing to experiment, take risksand sometimes fail.

America has always aspired to be a learning society. In fact, for many decades our education system, embodied particularly in science, technology, engineering and mathematicsor STEMfields, has been admired and emulated around the world. Nevertheless, our "learning society" is still a work in progress.

In fact, many would claim that our nation is in danger of losing its preeminent position as a world leader in excellence and innovation in education. Hence, the second half of my title: "Can America get its Bounce Back?" My answer to this question is a definite "Yes." I pose the question because I want to explore with you some ways to get American education back on trackand keep it there.

I begin with a conclusion from a government report on the American education system:

-

"...the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people. What was unimaginable a generation ago has begun to occur -- others are matching and surpassing our educational attainments."

This dire condemnation, all too familiar today, is from the report "A Nation at Risk," published twenty-six years ago in 1983. Growing competition from Japan, the Asian Tigers, and Germany created a wave of deep concern about the future of Americas prosperity. We hear similar warnings today, with China and India supplanting Japan and others as the growing threat.

Why the concern? Because... (and I quote from "A Nation at Risk" once more):

-

"Knowledge, learning, information, and skilled intelligence are the new raw materials of international commerce..." so "we must dedicate ourselves to the reform of our educational system for the benefit of all -- old and young alike, affluent and poor, majority and minority."

Over the years, scores of reports have described the same fault lines, cataloged the decline in educational excellence in America's schools, and echoed many of the recommendations of this seminal report. I'm sure you are familiar with all of these.

Slide words: ...the United States is the only country among the 30 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in which younger adults are less educated than the previous generation.

Slide image: photo showing a wall of flags from different countries

Slide image credit: © 2009 JupiterImages Corporation

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

And yet, a recent report from the National Commission on Adult Literacy1 finds that the United States is the only country among the 30 members of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in which younger adults are less educated than the previous generation. Something must changeand rapidly.

Slide title: Signs of Progress

Slide words: Rising Above the Gathering Storm

America COMPETES Act

Slide images: cover of "Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future" (left); photo of the U.S. Capitol building dome (right)

Slide image credits: The National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. (left); © 2009 JupiterImages Corporation (right)

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

There are signs of progress. Recently, the National Academies' report "Rising above the Gathering Storm," inspired the America COMPETES Act, which mandates a number of measures to strengthen STEM education and build the STEM workforce. And education plays a prominent role in Recovery Act funding.

Unfortunately, in times of economic distress, not everyone recognizes education's need for long-term and continuous improvement. Education may be put on the back burner in favor of short-term fixes to the economy. But consider this.

Slide title: Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America's Schools

Slide words:

* Achievement gap between U.S. and foreign students reduces GDP by $1.3 – $2.3 trillion.

* Cost of gaps among white, Latino and black students is between $310 and $525 billion, or 2 - 4% of GDP.

Slide image: cover of the report titled "The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America's Schools"

Slide image credit: McKinsey & Company

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

In April, the global consulting firm McKinsey added a new voice to the education dialogue with a study titled, "The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America's Schools."2 The stark conclusion of the McKinsey report is that "...educational gaps impose on the United States the economic equivalent of a permanent national recession."

According to the McKinsey study, the most significant costs are associated with an achievement gap between U.S. students and those of other nations, amounting to an estimated loss to Gross Domestic Product of between $1.3 and $2.3 trillion dollars in 2008.

The cost of gaps among white, Latino and black students are between $310 and $525 billion, or 2 to 4 percent of GDP. Given demographic trends in the U.S., these costs can only rise rapidly unless the gaps are closed.

Opportunity costs are among the most difficult figures to measure. They are real nonetheless. As the McKinsey study demonstrates, opportunity costs include the well-honed skills and expertise we lose when our educational institutions perform below optimal levels.

These losses can affect even the most diligent and promising students when institutions develop inertia and fail to change practices that have become outmoded or ineffective. And we have not even begun to measure the lost curiosity and aspirations that many students suffer.

The crescendo of voices calling for reform has reached a zenith. The American Chemical Society has long been a credible voice in this dialogue. Congress is concerned, and so is the President. In recent remarks to the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, President Obama put it this way: "The relative decline of American education is untenable for our economy, it's unsustainable for our democracy, it's unacceptable for our childrenand we can't afford to let it continue."3

Slide title: Aspirations of a Learning Society

Slide words:

Informed Citizens

Prosperity & Quality of Life

The Joy of Exploration

Slide images: photo of a town hall meeting in San Francisco (top left); photo of an early-morning band of showers blocking the rising sun just off the east coast of central Florida (top right); photo of a young student using a computer (bottom)

Slide image credits: Daniel Homsey, City and County of San Francisco (top left); © University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (top right); © 2009 JupiterImages Corporation (bottom)

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

President Obama's statement reflects the aspirations of a learning society. He recognizes the critical importance of economic competition to our nation's prosperity, but equally the value of a well-informed citizenry to participative democracy. And he understands that all children must have the opportunity to experience the exhilaration of learning and the deep satisfaction in being prepared to make their own contribution to society.

When we think in terms of a "learning society," we recognize that demands on educational institutions, and their teachers and faculty, have increased substantially. Educational institutions, at all levels, are being asked to address and resolve a growing variety of our society's most difficult challenges.

A focus on the learning society also points to the growing complexity of those challenges and the interconnections among them. The fact is that each spoke of the learning wheel works with the others to keep our society on a learning track.

We frequently speak metaphorically of "the pipeline" that supplies a steady stream of scientists and engineers to the workforce by moving raw talent through ever-higher levels of educational attainment.

Others have used less flattering metaphors. Peter Senge, an MIT management guru who helped pioneer the concept of a "learning organization" has another way of describing "the pipeline."

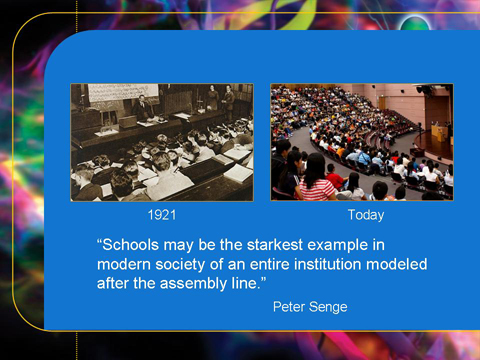

Slide words: "Schools may be the starkest example in modern society of an entire institution modeled after the assembly line." Peter Senge

Slide images: photo of students attending a lecture, circa 1921 (left); photo of students attending a lecture today (right)

Slide image credits: University of Bristol Library, Special Collections (left); teddY-riseD, via Flickr, Creative Commons license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.en (right)

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

"Schools," he says, "may be the starkest example in modern society of an entire institution modeled after the assembly line."

Pipeline thinking has dominated science and engineering workforce preparation and education for decades. We need to devise fundamentally new arrangements that convert "the pipeline" into learning environments and pathways that better suit our students and our times.

It will not be easy to forge new paradigms. But as one astute reformer has pointed out, "You can't wring your hands and roll up your sleeves at the same time." To paraphrase Langston Hughes, we should "not take 'but' for an answer."

Meaningful change will depend on at least two developments: our ability to discover fresh knowledge about how we learn, and how bold and persistent we are in bringing that understanding into the classroom, the laboratory, and the workplace.

We can only realize these developments if responsibility is shared widely. Although secondary and post-secondary education are the traditional province of chemistry, all chemists have a stake in STEM education at every level.

What can we say specifically about STEM education, particularly in the field of chemistryour immediate concern here today?

Several features of contemporary research present new challenges to chemistryindeed, to all fields. The convergence of disciplines and the cross-fertilization that characterize contemporary research have made collaboration across traditional borders a centerpiece of the science and engineering enterprise.

Discovery and innovation increasingly require the expertise of individuals with different perspectivesfrom different disciplines and often from different nations. Working together, researchers can accommodate more effectively the extraordinary complexity of today's science and engineering challenges.

Slide title: IGERT: Integrative Graduate Education & Research Traineeship

Slide image: (inset and background): photo showing a researcher in a cyberenvironment.

Slide image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

NSF programs such as IGERTIntegrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeshipshave encouraged the development of programs that provide opportunities for graduate students to work with peers across disciplinary borders. And IGERT programs are often useful in addressing institutional barriersyou might think of these as disciplinary "pipelines"that constrain interdisciplinary research.

Slide title: Collaboration

Slide words: Partnerships among schools, colleges, universities, private sector and government

Slide image: photo of ten hands one on top of another

Slide image credit: © 2009 JupiterImages Corporation

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

A feature shared by many NSF education programs is the development of partnerships among high schools, community colleges, universities, and the private sector. Collaborations with high schools can help reduce the barriers that students face in making the transition to colleges and universities. Almost 30 percent of students in their first year of college must take remedial science and math classes because they are not prepared for college-level courses.4 Bridging this gap requires greater collaboration among faculty at all levels.

Slide title: Research Experiences for Teachers

Slide words: Teachers at NSF's Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) site in Washington State

Slide images: photo of teachers learning about tree canopy research at the Wind River Canopy Crane near Carson, Washington (left); photo of Andrews Forest LTER Research Experience for Teachers (RET) fellow Kurt Cox showing teachers the field investigations he does with students at Andrews (right)

Slide image credits: Kari O'Connell, Oregon Natural Resources Education Program, Oregon State University (left); Susan Sahnow, Oregon Natural Resources Education Program, Oregon State University (right)

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

Partnerships can also provide enriched learning environments, including research opportunities for both students and faculty. NSF supports Research Experiences for Teachers and Research Experiences for Undergraduates as a means to provide first hand experience with both the rigors and the joys of research.

Slide title: Advanced Technology Education

Preparing a High-Tech Workforce

Slide images: five photos showing Advanced Technology Education (ATE) activities as follows:

- Energy & Environmental Technology: photo of two men at the Advanced Technology Environmental and Energy Center (ATEEC) installing solar panels (top left)

- Nanotechnology: photo of students at the National Center for Nanotechnology Applications and Career Knowledge (NACK) learning about vacuum technology (bottom left)

- Information & Security Technologies: photo of a CyberWATCH technician (center)

- Biotechnology: photo of a student checking protein concentrations at Genencor International, through the Advanced Technological Education Resource Center in Biotechnology called Bio-Link (top right)

- Marine Technology: photo of a Marine Advanced Technology Education Center (MATE) student using marine research equipment on a ship (bottom right)

Slide image credit: All photos from the "ATE Centers Impact 2008-2010" brochure, courtesy of The Advanced Technological Education Program

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

What about the private sector? Here, communication and cooperation between industry and educators at high schools, community colleges, and universities can inform the design of programs and provide opportunities for students to gain needed workplace skills.

One example is NSF's Advanced Technology Education programor, ATEwhich aims to improve the education of science and engineering technicians for the high-technology fields that drive our nation's economy.

ATE has a particular focus on community colleges, which often reach out to secondary schools as well. Community colleges now enroll 6.5 million degree-seeking students, or nearly half of all college undergraduates. The American Association of Community Colleges estimates that an additional 5 million students are enrolled in workforce training and other non-credit courses. The ATE program demonstrates that productive partnerships between employers and secondary schools, colleges and universities are not only possible, but desirable.

As you know, the National Science Foundation focuses on discovery, particularly through transformative research, on fostering knowledge and learning, and on building a STEM workforce of incomparable quality.

NSF supports research in learning, educational methods and tools, and assessment of educational programs. Advances in the science of learning provide the base on which effective practice is built. Credible educational reform will build upon a solid foundation of evidence integrated with theory.

Surely one of the grand challenges here is to build the capacity for research that connects basic science on language, cognition, and learning to improvement of educational outcomes in school settings5 at all levels. This is a long-term goal that is inherently interdisciplinary and complexbut also essential.

The NSF Science of Learning Centers program promotes long-term, interdisciplinary research to achieve a deeper understanding of the fundamental foundations of learning. The goal is to connect the research to specific scientific, technological, educational, and workforce challenges.

Of course, innovative teaching and curriculum development must be valued as significant faculty contributions and achievements, and rewarded as such. One inspiration for the NSF CAREER program: to encourage the integration of teaching and research on the part of promising early career researchers.

I've mentioned a few of NSF's flagship programs in order to illustrate collaborative possibilities, not to provide a complete catalogue. NSF has a distinctive role: to support the most innovative and promising ideas from the science and engineering research and education community. We are eager to collaborate with all of you in this endeavor.

Slide title: Can a society learn?

Slide images: photo of a U.S. flag; photo of students in the Science Partners for Inquiry-based Collaborative Education (SPICE) GK-12 program of the University of Florida (bottom left inset); photo of a crowd (top right inset); photo showing three students working with a microscope in a lab (bottom right inset)

Image credits: © 2009 JupiterImages Corporation (flag); Science Partners for Inquiry-based Collaborative Education (SPICE), University of Florida, Dr. D. Leveys (bottom left inset); © 2009 JupiterImages Corporation (top right inset); InSTEP Program, Florida Institute of Technology (bottom right inset)

Slide background image: photo of a cyberenvironment

Slide background image credit: Blake Harvey, NCSA

The concept of "the learning society" raises an intriguing question: Can a society learnas distinct from the individuals who constitute it? For good reasons, we most often focus on what can be accomplished for individuals or groups of individuals. That is the territory where our efforts can be implemented, tested and refined.

In one sense, to ponder this question is simply to ask whether our educational system and practices evolve, adapting to new understanding and changing circumstances. Much as we learn from the practice of science, our society can learn by asking questions about each and every principle and objective of how our educational system works at every level and across the nation.

As philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey once said, "Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself." We are all learners. It makes sense that what we require of our students, we should practice ourselves. We must become more knowledgeable, and that includes reaching out to other disciplines and the education community. We must be at ease with change and willing to accept risk. We must be proficient in innovation, comfortable with inclusiveness, both at home and abroad, and alert to the human and social aspects of our work. After all, this is exactly what we ask of our students and workers.

I suspect all of you are familiar with a common phenomenon on campuses. No matter how carefully paths are laid, students inevitably create new ones. In fact, the new paths seem to appear exactly where paths should have been in the first place. Cutting these new patterns is our challenge in preparing our students for the 21st Century workforce.

I look forward to your suggestions, and to deeper collaboration with the American Chemical Society and all of you who are a part of it. We must travel this road together.

NOTES

![]()

1. Reach Higher America: Overcoming Crisis in the U.S. Workforce; June 2008; last accessed 3 August 2009 at http://www.nationalcommissiononadultliteracy.org/report.html (Return to speech)

2. McKinsey & Co., http://www.mckinsey.com/clientservice/Social_Sector/our_practices/ Education/Knowledge_Highlights/Economic_impact.aspx; last accessed October 22, 2009. (Return to speech)

3. President Barak Obama, remarks to the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, March 10, 2009. (Return to speech)

4. National Center for Education Statistics, Remedial Education at Degree Granting Postsecondary Institutions in Fall 2000, (Boston, MA: National Center for Education Statistics, 2000). http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2004/2004010.pdf [No UPDATE available.] (Return to speech)

5. NSF Workshop Report, "Opportunities and Challenges for Language Learning and Education," September 5-7, 2007; http://www.nsf.gov/sbe/slc/NSFLanguageWorkshopReport.pdf (Return to speech)