We support research on human behavior and social organizations and how social, economic, political, cultural and environmental forces affect people's lives.

We aim to:

- Deepen our understanding of the human experience — how we think, learn and interact.

- Determine how fresh insights into human behavior can fuel innovations in technology.

- Explore patterns of stability and change to make society more secure and prosperous.

Studying the fundamental principles of human behavior has far-reaching implications, from identifying critical periods in child development to safeguarding the nation's troops, from exploring the origins of humankind to securing cyberspace, from understanding how the brain forms memories to how to get home with GPS.

What we support

Research on the brain and behavior

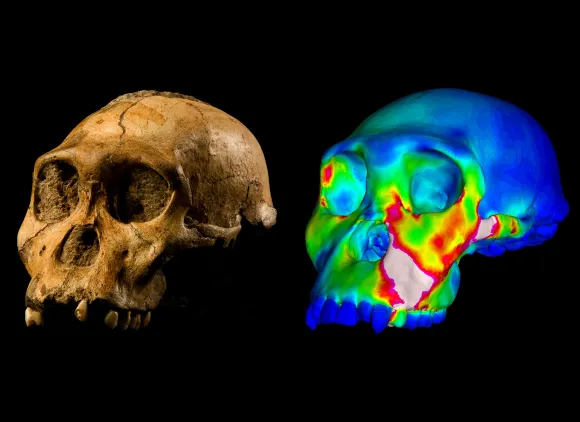

We support research in psychology, linguistics, anthropology and geography, including where humans came from, how the brain develops and learns, and how societies of the past lived.

Research on society and economics

We invest in the study of how societies, organizations and economies function, including how decisions are made and how scientific and technological progress are pursued.

Understanding the state of U.S. science and engineering

We collect and report data on the science and engineering workforce, U.S. competitiveness in science and technology and the progress of STEM education.

Broadening participation in the social sciences

We support research, training and infrastructure at minority-serving institutions and research on broadening participation in STEM education and the workforce.

Promoting ethical research conduct

We support research and training on the responsible conduct of research across scientific disciplines.

Featured news

Educational resources

View lesson plans, activities and multimedia for K–12 audiences that focus on exploring what makes us human.

View the resources