Next time you talk on a cell phone, hear a weather report, search the web, or get an MRI, remember the U.S. National Science Foundation helped make that all possible, and more.

Since 1950, NSF has invested in ideas and innovations that have shaped the modern world — pushing the boundaries of what's possible and deepening humanity's understanding of the world.

On this page you can explore NSF-supported research across all fields of science and engineering that power the American economy and touch everyone's lives.

On this page

On this page

Brought to you by NSF

Explore innovations and discoveries made possible through NSF support.

3D printing

3D printing is spurring a manufacturing revolution in the U.S. thanks to decades of NSF investments.

American Sign Language

NSF funding revolutionized education for deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in the United States.

Artificial intelligence

NSF funding built the foundation for technologies Americans use every day, such as digital assistants like Alexa and Siri, Face ID, image generators and chatbots like ChatGPT.

Bolstering small business

From artificial intelligence and energy to medical devices and semiconductors, NSF invests in deep-tech startups and small businesses working across all fields of science and technology.

CAPTCHA and reCAPTCHA

The tools that keep badly behaving bots from taking over the internet were invented by NSF-funded researchers.

CRISPR

NSF-supported research has advanced one of the sharpest tools in gene technology.

Cybersecurity

For decades, NSF has funded research to protect national and personal security in today's highly connected, digital world.

Deep-ocean exploration

Decades of NSF-funded deep-sea research and subseafloor ocean drilling reveal fundamental knowledge about the entire Earth system.

Detecting gravitational waves

Opened in 1999, NSF LIGO was the first to detect gravitational waves: ripples in space-time.

DNA amplification

Polymerase chain reaction, a lab technique that powers today's biotechnology sector, traces its roots to NSF funding.

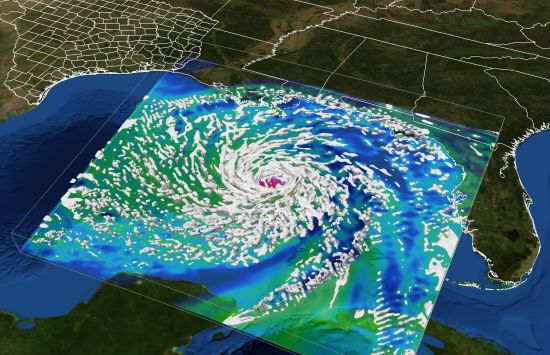

Doppler radar

Decades of NSF–funded research have improved the capabilities of the national Doppler radar network.

Duolingo

One of the most popular language-learning tools got its start from NSF funding.

Fusion energy

NSF's decades-long support for fusion R&D is paving the way toward an abundant, reliable power source to meet the world's growing energy demand.

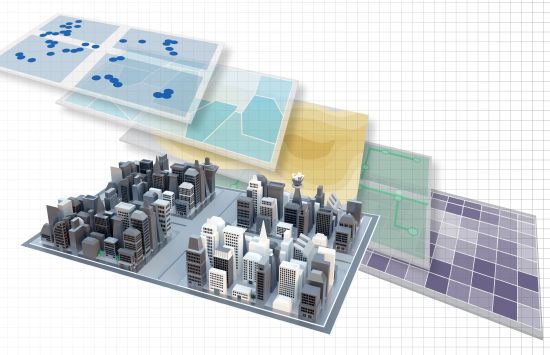

Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

NSF investments helped chart the course for the technologies that use spatial data to make people's lives more convenient.

The internet

Drawing on DARPA's pioneering support for early computer networking projects, NSF funding catalyzed the creation of today's internet.

Kidney matching

Decades of NSF funding for economic and algorithm research has facilitated thousands of lifesaving kidney transplants every year.

LASIK eye surgery

Decades of NSF funding supported the development of bladeless LASIK, which uses a laser instead of a scalpel to reshape a patient's cornea and improve their vision.

Learning beyond the classroom

Throughout its history, NSF has made the excitement of scientific discovery available to everyone by investing in children's TV programming, movies, museum exhibits and apps.

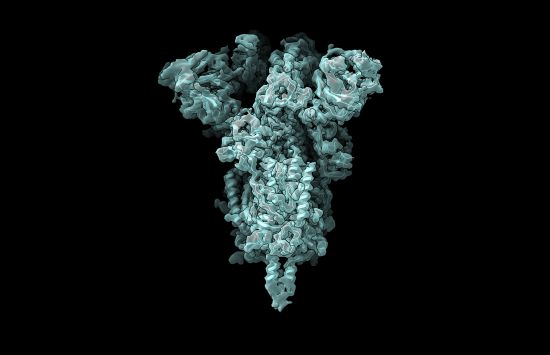

Protein Data Bank: Key to the molecules of life

NSF's decades-long support for the open-access database has facilitated pioneering scientific advancements and medical treatments.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

One of the most widely used medical imaging technologies is rooted in decades of NSF-powered research.

Natural hazards research: From risk to resilience

NSF-funded research on storms, wildfires and other natural hazards has saved lives, strengthened communities and reduced economic losses.

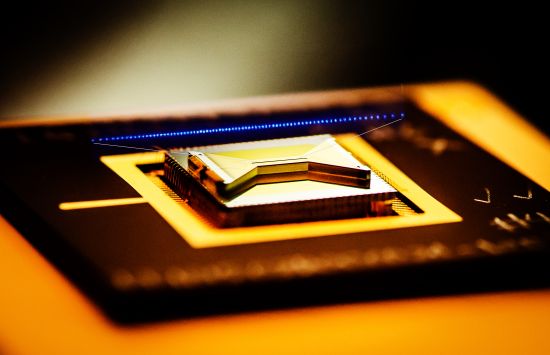

Quantum technology

The fruits of NSF's investments in quantum research are everywhere, from technologies that power modern life, like GPS, MRI and lasers, to next-generation computers, materials and sensors.

rDNA and insulin

NSF supported a landmark research project that revolutionized insulin drugs and jump-started the U.S. biotechnology industry.

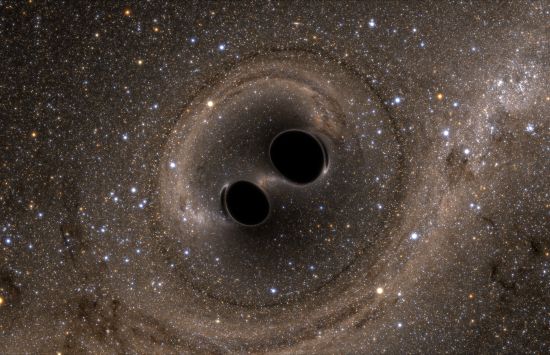

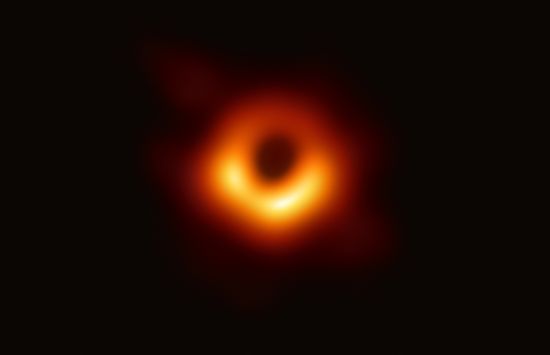

Seeing black holes

Thanks to NSF support, international researchers have now captured images of two black holes, including the one at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

Semiconductors

NSF–funded research has catalyzed breakthroughs in semiconductors, the chips that enable virtually all modern technology.

Smartphones

Smartphone technology traces its roots to decades of NSF funding, such as touchscreens, lithium-ion batteries and the internet.

Supercomputers

NSF's investments in cutting-edge supercomputers has catalyzed scientific breakthroughs and sharpened the nation's competitive edge.

NSF investments

Learn about NSF's ongoing investments and impacts in major areas of research and innovation.

NSF by the Numbers

Explore NSF's investments in science and engineering across the nation and in your state by fiscal year.

NSF Funded Projects (Awards)

Explore our database of funded projects to learn what we're doing across the U.S.

NSF Fact Sheets

Learn about NSF's investments in your state and how the agency is catalyzing innovation in emerging technologies.

NSF Public Repository

Explore NSF-funded scholarly publications and datasets.